ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

Benedikte Raft and Kolja Dahlin

This article explores the intersection of climate change, mobility, and gender in the Madhesh Province of Nepal, with a particular focus on the experiences of Maithili Dalit women, based on 19 semi-structured interviews conducted in 2024. It highlights how international labour migration, primarily undertaken by men, serves as a crucial survival strategy for families, while women remain behind to manage the household in the face of poverty and increasing climate risks. Utilising an intersectional approach, the article argues that (im)mobile Maithili Dalit women face poverty-induced vulnerabilities, which are amplified by climate change. Consequently, migration becomes a strategy for coping with these poverty-induced vulnerabilities. Privileging the voices and stories of Maithili Dalit women, the article attempts to understand those who are affected by climate change and international migration but are often absent from the political conversation and decision-making processes in a globalised world.

Keywords: climate change, im/mobilites, gender, Nepal

Suggested citation: B Raft and K Dahlin, ‘The Climate Crisis as a Poverty Crisis: How climate change amplifies (im)mobility and gendered vulnerabilities’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 25, 2025, pp. 12-30, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201225252

In the past two decades, public debates in the Global North have painted apocalyptic scenarios of massive waves of future migration due to climate change.[1] However, recent academic research argues that the links between migration and climate change may not be as straightforward.[2] Instead of viewing climate change as a primary driver of migration, researchers emphasise its amplifying effect on existing patterns of mobility and vulnerability, including the gendered risks induced by climate change.[3]

This article explores the intersection of climate change, mobility, and gender in Maithili traditions in the Madhesh Province of Nepal, focusing on how climate change and migration affect lower-caste Maithili Dalit women’s lives. Through fieldwork and interviews conducted in collaboration with the Danish Red Cross (DRC), the article underscores how international labour migration, primarily undertaken by men, serves as a crucial survival strategy for families, while women manage the household in the face of poverty and increasing climate risks. Poverty creates vulnerabilities, and these vulnerabilities are amplified by climate change. This vulnerability particularly affects women, who must endure not only poverty and the consequences of climate change but also systemic marginalisation in Maithili Dalit culture. Although the reality is more complex than the alarmist discourses advanced at the political level, we still need to engage with the relationship between climate change and migration. By understanding these links as interconnected and privileging Maithili Dalit women’s stories and strategies, we can enhance just practices and challenge the myths about the causal links between climate change and migration that dominate the climate–migration discourse.

We begin by reviewing relevant literature on the interlinkages between gender, the environment, and mobility. We then outline our research design and methodology, including a contextual overview of how climate change and migration intersect in Nepal’s Madhesh Province. Building on Christoffersen’s intersectional methodology,[4] we apply the gender–environment–mobility nexus as a conceptual and analytical approach to guide our iterative analysis of fieldwork data through three interrelated lenses: climate, mobility, and gender. This approach enables us to uncover how overlapping social, environmental, and structural pressures shape lived experiences, particularly for marginalised caste and gender groups, and to further advance our core argument.

Recent feminist migration scholars call for a more nuanced approach to understanding climate-related migration and relocation patterns. The nature of physical relocation can vary widely, ranging from short-term to long-lasting, occur seasonally or singularly, and happen by choice or by force.[5] This has led scholars to advocate for a focus on mobility rather than migration.[6] As a result, research has shifted towards embracing pluralism, recognising the inherently political nature of climate-related mobility, and understanding the diverse strategies local communities employ to navigate environmental changes.[7] Similarly, the mobility framework seeks to avoid constructing individuals as a homogenous ‘migrant mass’ devoid of any individualised decision-making regarding whether to relocate or stay put.[8]

Climate mobility is seen as an attempt to ensure the de-exceptionalism of international migration to instead understand climate movement as embedded in the already existing patterns of both mobility and immobility.[9] Boas et al. outline the advantages of adopting a climate mobilities viewpoint: firstly, it treats climate change as a relational phenomenon that varies by locality and ‘cannot be reduced to “impacts” that can be isolated, enumerated, modelled and hence predicted. … [Instead, it] exerts its influence through the matrix of social, economic, environmental, cultural, historical and political processes’.[10] This means that the climate mobility paradigm departs from more conventional migration understandings where migration is binary and can be predictably modelled. The mobility perspective thus shifts the focus from labelling migrants as ‘climate migrants’ towards a deeper understanding of how individuals perceive and respond to the effect of climate change in their lives and how it influences their mobility or immobility. It seeks to uncover the reasons behind people's decisions to move or stay, including the where, how, and why of these decisions.[11] Instead of establishing predictable connections, the notion of climate mobility prompts us to examine the intricate, day-to-day interactions between various forms and levels of mobility and climate change.[12] This perspective challenges the simplistic binary of seeing mobility as an active choice and immobility as a passive condition.

As we are interested in exploring climate mobility patterns in Maithili Dalit women’s lives, we address the concepts of climate, mobility, and gender not in isolation, but rather as entangled entities influencing each other. Recent literature suggests analysing these intersecting relationships through the lens of a climate–mobility–gender nexus, which explicitly examines how climate change exacerbates various forms of context-specific vulnerabilities connected to migration and gender.[13] This intersectional approach avoids the tendency to essentialise women as a homogenous group and overlook the multiple processes that constitute gendered subjects, identities, and bodies.[14] The dominant focus has been on the impacts of climate change on women, but greater attention is needed to how gender is intersected by axes (e.g. class, caste, age, etc.) as well as a relational analysis of both women and men across social categories in a changing climate.[15]

By applying the climate–mobility–gender nexus, we aim to move away from causal links and promote an intersectional view of gender and mobility to explain how climate change is linked to migration and gender. In this nuanced understanding, climate change is not perceived as the only source of risk or vulnerability, but rather as a risk amplifier.[16] Secondly, instead of assuming that men are mobile and agentic and women are neither, the climate–mobility–gender nexus allows for a greater focus on different forms of gendered dynamics and different ways to understand roles played in mobility. Overall, this article contributes to these previous intersectional findings in the literature by studying gender dynamics of migration and climate change in the Madhesh Province in Nepal.

Our fieldwork in Madhesh, Nepal, was part of a research project between the Danish Institute for International Studies and the Danish Red Cross (DRC).[17] The project sought to offer qualitative insights to the gendered dimensions of climate vulnerability, with a focus on how women experience and navigate intersecting challenges of environmental stress, poverty, caste-based exclusion, and male out-migration. In coordination with the DRC Nepal and Nepal Red Cross Society, Madhesh was selected as the primary research site due to its high levels of labour migration and acute exposure to climate-related hazards.[18] Situated in Nepal’s southern Terai region along the Indian border, Madhesh is geographically distinct from the country’s mountain areas. It forms part of the Eastern Gangetic Plain and shares deep historical, linguistic, and cultural ties with northern India.[19] Once unified under the medieval Maithili kingdom, the region continues to uphold Maithili customs and Hindu traditions, including caste hierarchies, which today remain deeply embedded in social life.[20] Despite Nepal’s constitutional commitments to equality, caste-based oppression persists, particularly for Dalit communities who continue to face political and social exclusion.[21] For Madheshi Dalits, especially women, structural marginalisation is further deepened by landlessness, tenuous citizenship status, and exclusion from broader inter-caste networks that facilitate access to opportunity and influence.[22] These social and economic barriers not only constrain everyday life but also shape how communities experience and respond to broader environmental and livelihood challenges.

Rivers have long been central to life in the Terai region, where cyclical flooding has traditionally been a part of the seasonal cycle. Yet increasingly erratic monsoon patterns and prolonged droughts, widely attributed to climate change, have begun to severely disrupt livelihoods.[23] Entire harvests and homes are often lost to sudden flooding, while dry spells leave families without sufficient water or food.[24] To cope with the new climate uncertainties, labour migration has emerged as a key adaptation strategy.[25] In Nepal, mobility patterns are evolving, with a notable shift towards internal migration from rural areas to urban centres, alongside a rising trend in international labour migration, particularly to destinations like India, Malaysia, and the Persian Gulf states.[26] The province of Madhesh mirrors these national mobility trends. In 2021 and 2022, most Nepali international labour migrants with formal labour permits were from Madhesh.[27] Over 40% of households in the region are classified as migrant households. Moreover, the province continues to rank among the poorest in Nepal, with one of the lowest Human Development Index (HDI) scores.[28]

Recognising these intersecting pressures, our research aimed to understand how women in migrant households, particularly those from marginalised Dalit communities, experience and negotiate these layered forms of vulnerability. To this end, we conducted a 12-day field trip to Nepal in February 2024. Although the fieldwork period was brief, close coordination and preparation, together with our Nepali Red Cross colleagues, ensured that the data gathering was as focused and meaningful as possible. Through continuous dialogue with the DRC’s country office in Nepal, along with volunteers from the Red Cross district office in Dhanusha, we identified the primary target groups for the data gathering as Dalit women impacted by mobility and climate change. The Dhanusha Red Cross volunteers helped identify the women and coordinated meetings with them before our arrival. We conducted 19 semi-structured interviews with Maithili Dalit women residing in the Kamala and Mukhiyapatti Municipalities of the Dhanusha District in Madhesh. All the women had husbands or sons working abroad, reflecting the centrality of migration in their household livelihood strategies. We focused on Dalit women because they often occupy the most vulnerable position at the intersection of caste, gender, and poverty, making them disproportionately exposed to both the impacts of climate change and of male out-migration. The interviews were carried out in close collaboration with both national and local Red Cross teams. Furthermore, semi-structured key informant interviews with village leaders and municipal officials were also conducted to gain broader contextual insights. A local translator fluent in Maithili facilitated communication during the interviews, ensuring that participants could speak comfortably in their native language.

For data processing, we followed an open coding strategy to remain closely attuned to the women’s narratives. As recurring patterns and themes emerged, we shifted to focused coding to identify the most significant categories and explore broader relationships and structures within the data.[29] Informants’ names have been anonymised for the purpose of this article, with descriptive footnotes included to provide contextual details about each woman, such as caste, age, and family circumstances.

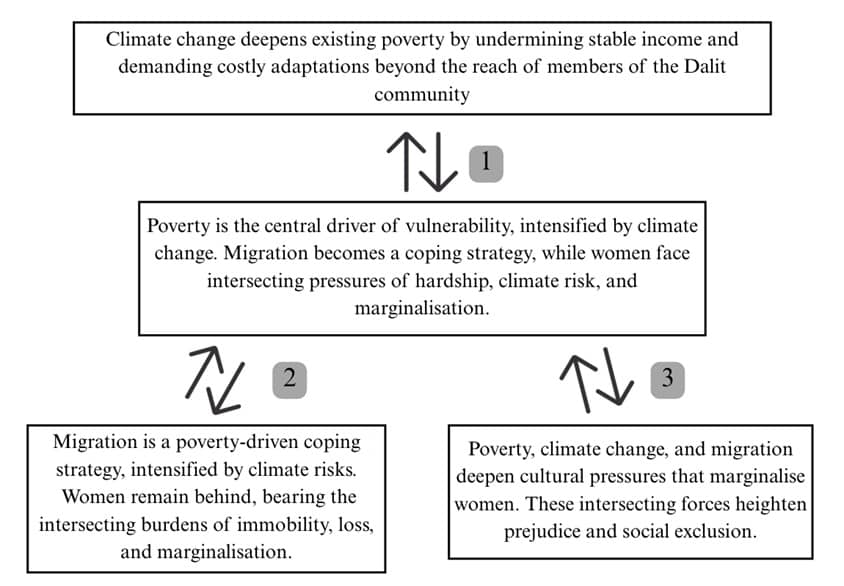

Our analytical framework will be structured around the three intersecting categories of the climate–mobility–gender nexus. This will help organise the core themes at play and further allow us to reflect on how other intersecting factors shape these relationships. Drawing on Christoffersen’s intersectional methodology,[30] we will examine the same data set three times, each section focusing on one of the nexus’s dimensions: (1) climate, (2) mobility, and (3) gender. By systematically shifting focus across these dimensions, we uncover overlapping narratives and insights, integrating reflections from interviews and field notes. Consequently, intersections between climate change and mobility, for instance, will be addressed both in the climate chapter and the mobility chapter, each offering distinct yet complementary analytical perspectives.

Figure 1: Visual representation of our intersectional framework.

As previously noted, floods have long been part of life in the Terai region, but their intensity and irregularity have increased markedly in recent years. The transformation has not gone from an absence of floods to their sudden occurrence, but rather from familiar, cyclical flooding to increasingly invasive and unpredictable events. Dalit women living along the Kamala River in Dhanusha District recounted how recent floods have swept through their communities with unprecedented force. During such events, many families had been forced to seek temporary refuge in nearby villages or adapt their homes by raising foundations in an attempt to reduce the damage. Parvati[31] described the impact vividly, ‘When rainy season comes, I have water coming here, so I don’t have a place to sleep or cook or live.’ In addition to displacement, floodings had disrupted agricultural cycles, reduced crop yields, and made it difficult to secure food. Laksmi[32] echoed this impact, stating, ‘Sometimes we have floods, so all the crops are destroyed.’ Although extreme weather was a constant feature in the lives of the women with whom we spoke, many struggled to fully grasp the phenomenon of climate change, and, for some, it was simply not a concern. The technical scientific explanations felt distant from their lives. Yet consequences were impossible to ignore. As Sita remarked, ‘Something is changing’.

Turning to the analysis of this article, rather than focusing on how these women experience the phenomenon of climate change as a whole, a more insightful approach is to examine how they experience the dramatic changes in weather patterns. In this section, we explore climate not as an abstract environmental issue but as a condition that deepens existing inequalities. We illustrate that the effects of climate change are best understood as a poverty issue. It worsens the scarcity of stable employment and makes income more precarious, while simultaneously demanding forms of adaptation, such as relocating, rebuilding, or changing livelihoods, that are often out of reach for poor Maithili Dalit women. In this way, climate change does not act alone; it compounds existing vulnerabilities, disproportionately affecting those least able to adapt.

The Dalit women we interviewed often worked as tenant farmers or wage labourers—forms of precarious employment that are particularly widespread among lower caste groups in Madhesh.[33] Tenant farming, which involves cultivating land owned by others in exchange for a portion of the yield or payment, is a common livelihood strategy in the region, especially among Dalit communities.[34] As Sugden notes, the agrarian structure across the Mithilanchal region is deeply shaped by long-standing class and caste-based inequalities, rooted in feudal state formations that historically empowered certain landed families as tax collectors and Dalit families as landless communities.[35] Within this already precarious livelihood system, the increasing frequency and severity of climate-related events, particularly floods and droughts, further reduce the availability of agricultural work. As environmental shocks destabilise crop cycles, they also erode the already limited employment opportunities for landless and land-poor women. As Kaditya[36] explained, ‘I am [...] affected because if floods or droughts are coming, I am not getting work.’ For her, the experiences of climate change translate into the ability to find daily wage labour. In this way, the concern for Maithili Dalit women is therefore not merely the changing weather but how these shifts intersect with agricultural livelihoods and reduce access to tenant or wage labour. Climate change is thus interpreted not through abstract environmental discourse but through the immediate lens of economic and health insecurity.

Adapting to climate challenges often depends on access to resources.[37] Whenever we asked the women what they needed to improve their everyday lives, most of them responded ‘a water pump’. Water pumps are not only useful to pump water out of houses and fields during floods, but they can also pump water onto fields during droughts. As such, they offer a measure of security and are considered a significant investment, often associated with wealth and status. Sarita,[38] who did not own a pump, explained, ‘A person who is very rich, they have their pump and all.’ Lacking a water pump was not just a symbol of economic disadvantage; it also had tangible consequences for families trying to cope with floods or droughts. While droughts complicate agricultural work, they are not insurmountable for those with the means to invest in necessary resources. The intersection of climate change and poverty becomes starkly visible in situations like these. Coping with the impacts of climate change often requires financial resources that Dalit women frequently lack. In Madhesh, adapting to climate challenges is not impossible, but it relies heavily on economic stability and access to essential resources.

Overall, this section has examined how environmental stressors intensified by climate change—particularly unpredictable and more extreme weather patterns—intersect with caste-based and socioeconomic inequalities. The impacts of climate change are not experienced in a vacuum; rather, they are mediated by poverty, landlessness, and limited access to adaptive resources such as water pumps. While wealthier landowners in Madhesh may mitigate environmental risks through infrastructure or irrigation, climate change is a persistent challenge embedded in the daily routines of many Maithili Dalit women, affecting their ability to find employment and secure basic necessities.[39] These climate-related pressures are thus best understood not as isolated environmental phenomena, but as forces that interact with entrenched social hierarchies, setting the stage for further analysis in the sections on mobility and gender.

On our way out of the house of Sunali,[40] we thanked her one last time for inviting us into her home. Sunali’s husband migrated to Malaysia around two years ago to work as a woodworker. The home was built on remittances he had sent from Malaysia. She did not have to work because his salary was good enough to take care of them both. She told us that she felt lonely and missed him. Even though he had migrated to another country to find employment, she was not permitted to leave their home. She was confined to a house built of money earned thousands of kilometres away.[41]

Migration was a constant presence in the villages we visited. Nearly every household shared stories of migration, ranging from long-term work abroad to seasonal labour in India—a practice that has persisted in the region for countless years.[42] Our initial observation was that women’s mobility often seemed inversely related to the migration of their husbands. As men migrated, women stayed behind. However, staying behind did not imply continuing life as before; rather, it often entailed a further restriction of women’s mobility. The phenomenon illustrated in Sunali’s story must be understood within a broader context of gendered and caste-based restrictions. In Madheshi communities, many women are only permitted to leave the home when accompanied by their husbands or elder family members, a condition rendered more restrictive by the absence of male relatives when they are working thousands of kilometres away.[43] These accounts reflect what Zharkevich identifies as the relational construction of (im)mobility in rural Mid-Western Hills of Nepal, in which women’s virtue is symbolically tied to their physical presence in the home, reinforcing ideals of femininity rooted in domesticity and respectability.[44] Even in the context of male out-migration, which sometimes necessitates greater female participation in economic or public life, traditional gender ideologies often persist, if not intensify, particularly for poor and marginalised women like those from Dalit communities.[45]

Despite cultural norms shaping immobilities, the poorest Dalit women are often forced to leave their homes in search of wage labour. In the districts of Dhanusha and Mukhiyapatti, this did not translate into empowerment. Instead, it exposed them to increased vulnerability and community stigma. Asmita,[46] who had migrated to India for work, described how even expressing a desire to migrate was considered inappropriate for women. Kaditya[47] echoed this sentiment: ‘If I am planning to move, the community members will feel I am quite odd, point fingers at me (…) so that’s why I’m not going.’ As such, the mobility of Dalit women must be understood not merely as a matter of physical movement but as embedded in intersecting structures of caste, gender, poverty, and community norms shaping women’s experiences and decisions to move.

Although shaped by social norms and structural inequalities, Maithili Dalit women’s apparent immobility should not be conflated with passivity or lack of agency. While the women themselves rarely migrated, many described decisions around male out-migration as collective, involving discussions with husbands and family elders. In the Madheshi context, such decisions are often negotiated at the household level through complex gendered dynamics. Although men typically hold more authority, several women emphasised their role in influencing, and at times initiating, migration-related choices. However, this does not imply equal power in decision-making, as these conversations unfolded within broader dynamics of traditional patriarchal household hierarchies where women’s voices were negotiated rather than guaranteed. Nevertheless, it nuances reductive narratives that portray women as entirely passive or excluded from processes of mobility.

Many of the women recognised the importance of sending their husbands and sons to work abroad, but this did not make the decision any easier. ‘When my husband left, I cried for three weeks’, Urja[48] shared. The women were deeply aware of the dangers, recounting harrowing stories of migrants being killed, and expressed constant worry for the safety of their loved ones abroad. For some, these fears became a devastating reality. Many women in the community had been widowed, and in some cases, the circumstances of their husbands’ deaths remained unclear. Ganga[49] learnt about her husband’s death through Facebook, and she expressed to us: ‘His body might still be somewhere in India.’ Saraswati,[50] an elderly woman, also shared how her son came home from Qatar due to mental issues. She did not know what had happened to him. He came home with nothing, and although his remittances had been used to build an elevated house, she now had to take care of him and pay back the loans it took to send him abroad while also ensuring an income for the family to survive.

These scenarios underscore that migration is not simply a long-term investment but also a gamble shaped by emotional precarity, debt, and loss. While remittances may offer critical lifelines, the burden of managing the emotional and economic uncertainties and consequences of migration often falls on the women who remain behind. Lei and Desai’s research in India shows that women whose husbands migrate often report worse health outcomes than those whose husbands remain.[51] Larger and consistent remittances may alleviate some of these pressures by reducing women’s hardships; however, when remittances are low or irregular, they tend to intensify both emotional strain and material hardship.[52] Yet the alternative is rarely viewed as better. Although migration projects can come at great costs, opting against them comes with great economic downsides as well. As Sarita, who had six daughters, explained, not having a son meant having no access to remittances at all. Her open disappointment in not bearing sons reflected a deeper economic grief: ‘So you pray for a son because then you get money; you earn money from them.’ In her words, sons represented income, while daughters were framed as financial burdens. When asked later about the main challenges she faced, her answer was blunt: ‘daughters’. Her response underscores how deeply intertwined gendered expectations, migration, and economic survival are in the everyday lives of Maithili Dalit women.

The reason why international labour migration is a gamble worth taking is the remittances. A stable flow of them enables significant investments, such as building elevated houses—an essential climate adaptation, as Sunali[53] explained: ‘So he sent money, then we built this house.’ Even if not its primary purpose, migration often serves as a means of adapting to climate change, as remittances help families afford both daily needs and larger investments. However, migration is a gamble, and the intersections between poverty, caste-based discriminations, gender, and mobility are present in the examples above. The economic advantage might land families in debt spirals despite an otherwise successful migration project. To harness the promise of migration, a family in Madhesh requires either husbands or sons, access to resources to fund the journeys without ending in debt traps, and luck that the remittances keep flowing. Although Maithili Dalit women generally do not engage in migration, mobility patterns in Madhesh cannot be understood without examining the various ways in which women are embedded in the out-migration of their male family members: by taking part in the decision-making process over whether a family member will migrate for work; by missing their husbands or sons but still needing them to be abroad due to the essential income their remittances generate; and by being left to deal with the consequences of failed migration projects.

Having established that the impacts of climate change on livelihoods in Madhesh are deeply entangled with caste and poverty, and recognising women’s role in broader mobility patterns, a central question emerges: how are Maithili Dalit women rendered particularly vulnerable at the intersections of gender, climate, and migration? Here, culture plays a central role. The cultural norms and traditions that structure Maithili women’s lives shape how overlapping hardships like climate-induced floods, poverty, lack of work, etc. are understood, endured, and responded to, reinforcing gendered hierarchies while also defining the terms of survival and agency.[54]

Engaging with questions on the intersecting linkages between gender and cultural conditions in the discussions of the livelihoods of Maithili Dalit women, one custom stands out as central to the families’ lives: dowries. The dowry system is deeply entrenched in Maithili culture, emblematic of both societal norms and familial expectations.[55] Over time, the costs of dowries have escalated, imposing substantial financial strain on families.[56] Our translator recounted how the system brought ‘mental and physical torture’, while all women interviewed noted that their families had to take out loans to afford dowry payments. For the women, a daughter not only represented an economic liability due to dowries but also the absence of a future caregiver.

In rural Maithili culture, caregiving typically relies on familial structures, with daughters moving to their in-laws’ household post-marriage. This dynamic leaves families with daughters alone and unsupported in their later years. Sarita who only had daughters underscored this anxiety: without a son contributing financially or a daughter-in-law to provide care, her future felt uncertain. The financial and caregiving void left by this system creates layers of vulnerability for Maithili Dalit women across their lifespans, compounded by poverty and precarious economic conditions.

To further understand women’s immobility and confinement requires a nuanced appreciation of cultural norms and traditions. In Maithili culture, a woman’s physical immobility within the household signifies that she is well taken care of and that her family is affluent enough to support her without requiring her to engage in labour outside the home. As our translator explained one day to us: ‘[If] a Maithili woman’s hands are soft, other people can see that she is well taken care of’, indicating the need for women to remain untouched by paid labour and other harsh realities from the outside world. For wealthy women, immobility is a status symbol; for poor women, it is enforced deprivation. However, this system experiences significant strain under pressures from precarious working conditions, at home and abroad, as well as climate change. The following story emphasises why that is the case:

Jyoiti[57] had spent nearly her entire life as a widow. Her husband had migrated to work in India forty years ago but tragically died in a work accident due to medical issues after returning home. She was only in her early twenties when he passed away. She explained to us how she was not allowed to partake in any village ceremonies after her husband died. This is because, in Maithili Dalit culture, widows are not allowed to take part in any social activities. They are further restricted in their diet and only allowed to eat vegetarian foods. Jyoiti expressed how: ‘I have all kinds of problems. I don’t have a home. I don’t have clothes to wear. I don’t have food. There is no one to help me.’ Because Jyoiti had no husband to take care of her, she often had to leave her home, but this was frowned upon by the local community.

Two years ago, her house was destroyed in a flood, and with little donations from the municipality she was able to build a new roof. However, many parts of the house were still destroyed when we spoke to her. Deprived of economic and cultural resources, she was left alone and unable to secure a safe and stable life for herself. For her, stress was not the fear of being attacked or physically harmed. Instead, it was the uncertainties induced by climate change and a lack of income, along with caste and cultural restraints, that made her life insufferable.

Jyoiti’s story illustrates how cultural conditions fail to accommodate the absence of a husband, who is traditionally seen as the provider. The cultural arrangements she described were likely shaped in a time when male out-migration was less prevalent, and they have not been adapted to the current realities of life in Madhesh. Due to economic hardship, women like Jyoiti are consequently forced to step outside of their traditional roles and confront a dual burden: not only do they need to bear all responsibilities of managing their households, but they also face judgements for not conforming to the societal ideal of women’s immobility. This burden is further exacerbated by climate-induced risks. As illustrated in Jyoiti’s story, the intersection between mobility, climate change, and poverty can entrench already existing vulnerabilities and inequalities for women, marginalising them further. The Maithili culture places a high value on family and collective unity. When women find themselves alone due to reasons such as migration and poverty, they face different forms of marginalisation and are left to survive without any support or care from others. Men can also be poor, but they are still allowed to access spaces of participation such as leaving their homes to find work. Women, particularly those living without a husband, are left alone, in a form of double-sided misery: either stay at home without means to secure an income or leave the home and be confronted with the stigmas surrounding women in public spaces.

Furthermore, if Maithili Dalit women would venture outside to work, enduring the stigma from the Maithili communities, they would still be Dalits. Dalit communities are restricted from several occupations, leaving them with only a few low-paying jobs.[58] This systemic exclusion from more respected professions severely limits their economic mobility and reinforces their marginalised status. Atreya et al. find that the total income of Nepali Dalit households headed by single women is approximately 23% less than that of other Dalit households.[59] This suggests that widows like Jyoiti and Ganga have fewer work opportunities and experience greater social burdens. As Laksmi[60] expressed: ‘(...) being a single woman, being low-caste, you face such kind of abuse and such kind of exploitation.’ This sentiment underscores the daily discrimination that Dalit women endure, both within their communities and in the broader society. The intersection of caste, class, and gender not only restricts their employment opportunities but also subjects them to heightened vulnerability to violence and exploitation. Studies have shown that Indian Dalit women are disproportionately affected by sexualised violence and are often denied justice due to systemic biases.[61] These entrenched barriers illustrate the profound structural inequalities that hinder Dalit women’s access to economic and social advancement.

To summarise, in Madheshi communities, poverty puts pressure on the cultural dynamics, which further marginalises Dalit women. The examples above not only illustrate the intrinsic link between gender and culture but also how economic and environmental shocks can distort existing gendered and cultural structures. In that way, women are simultaneously supposed to be ‘unspoilt’ and bear the role of ‘economic ruin’ due to dowry payments. These pressures are further amplified due to the job uncertainty created by climate change and the necessity of migration to sustain an income. The intersecting vulnerabilities of gender, culture, climate, and poverty thus result in heightened prejudice against women, increasing their vulnerability and risk of social exclusion.

The aim of this article was to understand the intersection of climate change, migration, and gender in shaping the lives of Maithili Dalit women in Madhesh. Drawing on intersectional methodology and qualitative fieldwork, we analysed the same dataset iteratively through three lenses: climate, mobility, and gender. This approach allowed us to identify overlapping pressures and dynamics that structure these women’s everyday lives.

Our findings demonstrate that the effects of climate change in Madhesh are best understood as a poverty issue. Climate change exacerbates the scarcity of stable employment, drives income precarity, and creates adaptation demands, such as rebuilding or relocating, that are often inaccessible to poor Dalit women. In this context, migration—primarily undertaken by men—emerges not as a direct response to climate threats, but as a coping strategy for enduring poverty and sustaining family livelihoods. Yet while men leave, women remain, to face not only the consequences of climate stress and economic hardship but also deeply entrenched gendered and cultural expectations.

At the same time, Maithili Dalit women are not passive or immobile. They play central, if constrained, roles in managing households, participating in migration-related decisions, and absorbing the emotional and material risks associated with (im)mobilities. Their immobility is not a sign of disconnection from migration but a result of intersecting structures of caste, gender, poverty, and local norms. Ultimately, climate change does not act in isolation; it compounds pre-existing vulnerabilities and sharpens the inequalities that already shape people’s lives. For Maithili Dalit women, vulnerability is not just about environmental exposure but about navigating a landscape where economic marginalisation, caste-based discrimination, and immobility are mutually reinforcing. Recognising this complexity is essential in climate change adaptation and mitigation approaches centring those most affected by overlapping crises of climate, labour, and inequality. We argue that only by understanding these intersections between gender, caste, poverty, (im)mobility, and climate is it possible to fully grasp how Maithili Dalit women are affected by the interplay between climate change and migration. Any attempt to view these issues in isolation would obscure the deeply relational and intersectional nature of their vulnerability.

This article is based on a Master’s thesis from the Department of Political Science at the University of Copenhagen and has been rewritten for publication. The research was developed in collaboration with DIIS Senior Researcher Sine Plambech and Postdoctoral Researcher Sofie Henriksen. We would also like to extend special thanks to Gender Officer Dhana Owd from the Danish Red Cross in Nepal and to the volunteers from the Red Cross Dhanusha District Office for their invaluable assistance in the field. Finally, we express our deepest gratitude to our thesis advisor, Prof Maja Zehfuss, for her guidance and support throughout the research process.

Benedikte Raft is a PhD Fellow at the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Political Science. Email: bmr@ifs.ku.dk

Kolja Dahlin obtained his MA in Political Science from the University of Copenhagen. Email: kolja.dahlin@gmail.com

[1] J Warner and I Boas, ‘Securitization of Climate Change: How Invoking Global Dangers for Instrumental Ends Can Backfire’, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, vol. 37, no. 8, 2019, pp. 1471–1488, https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654419834018; G Bettini, ‘Climate Barbarians at the Gate? A Critique of Apocalyptic Narratives on “Climate Refugees”’, Geoforum, vol. 45, 2013, pp. 63–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.09.009.

[2] I Boas, N de Pater, and B T Furlong, ‘Moving Beyond Stereotypes: The Role of Gender in the Environmental Change and Human Mobility Nexus’, Climate and Development, vol. 15, no. 1, 2023, pp. 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2022.2032565.

[3] F Sultana, ‘Gendering Climate Change: Geographical Insights’, The Professional Geographer, vol. 66, no. 3, 2014, pp. 372–381, https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2013.821730; C G Goodrich, P B Udas, and H Larrington-Spencer, ‘Conceptualizing Gendered Vulnerability to Climate Change in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: Contextual Conditions and Drivers of Change’, Environmental Development, vol. 31, 2019, pp. 9–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2018.11.003; S Arora, ‘Intersectional Vulnerability in Post-Disaster Contexts: Lived Experiences of Dalit Women After the Nepal Earthquake, 2015’, Disasters, vol. 46, no. 2, 2022, pp. 329–347, https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12471; S Leder, ‘Beyond the “Feminization of Agriculture”: Rural Out-Migration, Shifting Gender Relations and Emerging Spaces in Natural Resource Management’, Journal of Rural Studies, vol. 91, 2022, pp. 157–169, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.02.009; I Boas et al., ‘Climate Mobilities: Migration, Im/Mobilities and Mobility Regimes in a Changing Climate’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol. 48, no. 14, 2022, pp. 3365–3379, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2066264.

[4] A Christoffersen, ‘Intersectional Approaches to Equality Research and Data’, Advance HE, April 2017, retrieved 29 March 2024, https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/intersectional-approaches-equality-research-and-data.

[5] Sultana.

[6] H Wiegell, I Boas, and J Warner, ‘A Mobilities Perspective on Migration in the Context of Environmental Change’, WIREs Climate Change, vol. 10, issue 6, 2019, pp. e610, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.610; I Boas et al., ‘Climate Change and Internal Migration Intentions in the Forest-Savannah Transition Zone of Ghana’, Population and Environment, vol. 35, no. 4, 2014, pp. 341–364, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-013-0191-y; G Cundill et al., ‘Toward a Climate Mobilities Research Agenda: Intersectionality, Immobility, and Policy Responses’, Global Environmental Change, vol. 69, 2021, pp. 102315, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102315.

[7] Boas et al., 2022; Wiegell et al.

[8] M Sheller, Mobility Justice, Verso, London, 2014; Bettini.

[9] J Schapendonk, M Bolay, and J Dahinden, ‘The Conceptual Limits of the “Migration Journey”: De-Exceptionalising Mobility in the Context of West African Trajectories’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol. 47, no. 14, 2021, pp. 3243–3259, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1804191.

[10] Boas et al., 2022, pp. 3368–3369.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Boas et al., 2023.

[13] Sultana; Goodrich et al.; Arora.

[14] K Davis, ‘Intersectionality as a Buzzword: A Sociology of Science Perspective on What Makes a Feminist Theory Successful’, Feminist Theory, vol. 9, no. 1, 2008, pp. 67–85, https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700108086364; A Kaijser and A Kronsell, ‘Climate Change through the Lens of Intersectionality’, Environmental Politics, vol. 23, no. 3, 2014, pp. 417–433, https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.835203.

[15] Sultana, p. 374.

[16] P Lama, M Hamza, and M Wester, ‘Gendered Dimensions of Migration in Relation to Climate Change’, Climate and Development, vol. 13, no. 4, 2021, pp. 326–336, https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1772708.

[17] S Henriksen, S Plambech, K Dahlin, and B Raft, Climate Migration Amplifies Gender Inequalities, Migration and Global Order Research Unit, Danish Institute for International Studies, 2024, https://research.diis.dk/en/publications/climate-migration-amplifies-gender-inequalities.

[18] F Clement and F Sugden, ‘Unheard Vulnerability Discourses From Tarai-Madhesh, Nepal’, Geoforum, vol. 126, 2021, pp. 68–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.07.016.

[19] K C Samir, ‘Internal Migration in Nepal’, in M Bell et al. (eds.), Internal Migration in the Countries of Asia: A Cross-national Comparison, Routledge, 2020, pp. 249–267, pp. 250; M Witzel, ‘Tracing the Vedic Dialects’, in C Caillat (ed.), Dialectes dans les Littératures Indo-Aryennes, Paris, 1989, pp. 97–264; M Jha, Anthropology of Ancient Hindu Kingdoms: A Study in Civilizational Perspective, M.D. Publications Pvt., New Delhi, 1997, pp. 55–56.

[20] D Gellner, J Pfaff-Czarnecka, and J Whelpton, Nationalism and Ethnicity in a Hindu Kingdom: The Politics and Culture of Contemporary Nepal, Taylor & Francis, London, 2012, p. 251; D Chaudhary, Tarai/Madhesh of Nepal. An Anthropological Study, Ratna Pustak Bhandar, Kathmandu, 2011; K P Pandey, ‘Madheshi Dalit Women’s Access to Citizenship and Livelihood Alternatives in Nepal’, Contemporary Voice of Dalit, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/2455328X241258001.

[21] M Subedi, ‘Caste System: Theories and Practices in Nepal’, Himalayan Journal of Sociology & Anthropology, vol. 4, 2010, pp. 134–159, https://doi.org/10.3126/hjsa.v4i0.4672.

[22] Pandey.

[23] P Bolte, S Marr, and S M Y Chaw, At the Frontlines of the Climate Crisis: Scoping Study for the Development of a Climate Resilience Programme in Asia (Afghanistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Myanmar), Danish Red Cross, Copenhagen, 2023.

[24] Ibid.

[25] A Maharjan et al., ‘Can Labour Migration Help Households Adapt to Climate Change? Evidence from Four River Basins in South Asia’, Climate and Development, vol. 13, issue 10, 2021, pp. 879–894, https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1867044.

[26] S Bhattarai, B Upadhyaya, and S Sharma, State of Migration in Nepal, Centre for the Study of Labour and Mobility, Kathmandu, 2023; L Sherpa and G Bhatrai Bastakot, Migration in Nepal through the Lens of Climate Change, Climate Action Network South Asia (CANSA), January 2021, p. 11.

[27] International Organization for Migration (IOM), Policy Brief: Migration and Skills Development, IOM Nepal, 2022.

[28] Ibid.; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Nepal Multidimensional Poverty Index 2021: Analysis Towards Action, Government of Nepal, Kathmandu, 2021, https://www.undp.org/nepal/publications/nepal-multidimensional-poverty-index-2021.

[29] Clement and Sugden, p. 69.

[30] Christoffersen.

[31] Dalit, age unknown, husband works in India.

[32] Dalit, aged 35, husband died while working in Qatar.

[33] Pandey, p. 8.

[34] F Sugden, ‘A Mode of Production Flux: The Transformation and Reproduction of Rural Class Relations in Lowland Nepal and North Bihar’, Dialectical Anthropology, vol. 41, no. 2, 2017, pp. 129–161, pp. 142, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10624-016-9436-3.

[35] Ibid.; F Sugden, ‘Pre-Capitalist Reproduction on the Nepal Tarai: Semi-Feudal Agriculture in an Era of Globalisation’, Journal of Contemporary Asia, vol. 43, issue 3, 2013, pp. 519–545, https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2013.763494; Clement and Sugden.

[36] Dalit, aged 30, husband previously worked in Saudi Arabia.

[37] Wiegell et al.

[38] Dalit, aged 60, has only daughters.

[39] F Sugden, ‘Neo-Liberalism, Markets and Class Structures on the Nepali Lowlands: The Political Economy of Agrarian Change’, Geoforum, vol. 40, issue 4, 2009, pp. 634–644, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.03.010; F Sugden, Landlordism, Tenants and the Groundwater Sector: Lessons From Terai-Madhesh of Nepal, IWMI Research Report 162, International Water Management Institute, Colombo, 2014.

[40] Dalit, aged 20, husband works in Malaysia.

[41] Excerpt from field notes, 15 February 2024.

[42] Y Gautam, ‘Seasonal Migration and Livelihood Resilience in the Face of Climate Change in Nepal’, Mountain Research and Development, vol. 37, no. 4, 2017, pp. 436–445, https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-17-00035.1.

[43] S Maharjan and R K Sah, ‘Madheshi Women in Nepal’, in R K Chaudhary, P Yadav and S R Chaudhary (eds.), The Landscape of Madhesh: Politics, Society and Economy of the Plains, Nepal Madhesh Foundation, 2012, pp. 119–149.

[44] I Zharkevich, ‘Gender, Marriage, and the Dynamic of (Im)Mobility in the Mid-Western Hills of Nepal’, Mobilities, vol. 14, no. 5, 2019, pp. 681–695, https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2019.1611026.

[45] G Shrestha, E L Pakhtigian, and M Jeuland, ‘Women Who Do Not Migrate: Intersectionality, Social Relations, and Participation in Western Nepal’, World Development, vol. 161, 2023, pp. 106109, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106109.

[46] Dalit, aged 35, originally from India.

[47] Dalit, aged 30, husband previously worked in Saudi Arabia.

[48] Dalit, aged 32, husband works in India.

[49] Dalit, aged 43, son works in Malaysia. Husband used to work in India until he was murdered.

[50] Dalit, aged 70, son migrated to Qatar but returned.

[51] L Lei and S Desai, ‘Male Out-Migration and the Health of Left-Behind Wives in India: The Roles of Remittances, Household Responsibilities, and Autonomy’, Social Science & Medicine, vol. 280, 2021, pp. 113982, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113982.

[52] A Maharjan, S Bauer, and B Knerr, ‘Do Rural Women Who Stay Behind Benefit from Male Out-Migration? A Case Study in the Hills of Nepal’, Gender, Technology and Development, vol. 16, issue 1, 2012, pp. 95–123, https://doi.org/10.1177/097185241101600105.

[53] Dalit, aged 20, husband works in Malaysia.

[54] Pandey; S P Subedi, ‘The Status of Dalit Women in Nepal’, in J Rehman, A Shahid, and S Foster (eds.), The Asian Yearbook of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law, Brill | Nijhoff, Leiden, 2022, pp. 43–53, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004520806_004.

[55] Maharjan and Sah, p. 141.

[56] Sugden, 2017, p. 140.

[57] Dalit, aged 60, husband died from medical issues after working in India.

[58] Pandey, p. 4.

[59] K Atreya et al., ‘Dalit’s Livelihoods in Nepal: Income Sources and Determinants’, Environment, Development and Sustainability, vol. 25, 2023, pp. 12629–12657, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02582-2.

[60] Dalit, aged 35, husband died working in Qatar.

[61] N S Sabharwal and W Sonalkar, ‘Dalit Women in India: At the Crossroads of Gender, Class, and Caste’, Global Justice: Theory Practice Rhetoric, vol. 8, no. 1, 2015, pp. 44–73, https://doi.org/10.21248/gjn.8.1.54.