ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

Bond Benton and Daniela Peterka-Benton

The QAnon conspiracy threatens anti-trafficking education because of its broad dissemination and focus on a range of myths about trafficking. These myths are rooted in historic and ongoing misinformation about abductions, exploitation, and community threats. This article examines the extent of QAnon’s co-optation of human trafficking discourses and evaluates its connection to trafficking myths, particularly related to gender, race, class, and agency. From this perspective, the article considers how anti-trafficking education can respond to these myths and build a pedagogy in the age of Q.

Keywords: QAnon, conspiracy theory, anti-trafficking education, trafficking myths

Please cite this article as: B Benton and D Peterka-Benton, ‘Truth as a Victim: The challenge of anti-trafficking education in the age of Q’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 17, 2021, pp. 113-131, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201221177

A 2020 post in a New Jersey Moms Facebook group reads, ‘just a quick heads up my daughter was in the beauty supply down by [H]ome [D]epot and in came a large gentleman with a mask that only showed his eyes and wearing a snowsuit. He proceeded to follow my daughter through the store […], all the while motioning to a car a grey Toyota Camry type vehicle with tinted windows and a bad exhaust (note this is common with sex traffickers), that was waiting for him outside.’ Although a concerned post about a scary interaction in a beauty supply store is not out of the ordinary, declaring the Toyota Camry the car of choice for ‘sex traffickers’ appears a bit surprising. Or is it? In recent years, a seemingly new group of anti-trafficking ‘experts’ has flooded social media. They share tips about how to spot traffickers, keep children on playgrounds protected from abductions and, more broadly, how to ‘save the children’. This social media call for concerned mothers to join the crusade against trafficking emerged from a fringe conspiracy theory about ‘an elite group of child-trafficking paedophiles […] ruling the world for decades’.[1] This conspiracy theory has become the global QAnon movement.

What appears to be an absurd online conspiracy has inspired actions and activity in the ‘real world’. Q’s first official online post was made in 2017, but the conspiracy is largely an extension of several older conspiracies. These include Pizzagate, which alleged that coded words and symbols found in hacked emails of John Podesta, chairman of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign, point to a secret child trafficking ring in the basement of the Washington, D.C. pizza restaurant, Comet Ping Pong.[2] The story was further amplified by far-right media personalities such as Alex Jones and automated social media accounts or bots. What many ignored as an absurd online conspiracy turned potentially deadly on 16 December 2016, when Edgar Maddison Welch drove to Washington D.C. from North Carolina armed with an AR-15 rifle and a .38 calibre handgun to investigate the pizza restaurant himself. He entered where families were enjoying their meals and made his way towards the back of the building to locate the secret entrance to the basement ‘dungeon’. Fortunately, no one was hurt during the incident, but it became abundantly clear how online conspiracies could incite real actions. In fact, an FBI bulletin dated 30 May 2019 acknowledged the threat posed by QAnon, stating, ‘These conspiracy theories very likely encourage the targeting of specific people, places, and organizations, thereby increasing the likelihood of violence against these targets.’[3]

In addition to influencing individuals’ actions, the trafficking conspiracies shared in support of Q can shape the perceptions of various audiences, including students in classrooms, participants in workshops, and viewers of outreach content. The effects of misinformation on anti-trafficking efforts are not abstract. Speaking anonymously because of Q threats she has received, a senior staffer at a national anti-trafficking organisation stated, ‘It definitely impedes our work when we’re getting harassed and trolled over misinformation campaigns… It’s exhausting work. It’s traumatic work. It’s something that all of us do because there’s such an extreme need in our communities and around the country. And this just makes it all so much harder.’[4] As the QAnon conspiracy threatens to disrupt anti-trafficking education, this paper will examine the QAnon conspiracy and the historical trafficking myths that preceded it. From there, we will investigate how the focus of anti-trafficking education may leave educators unprepared to respond to conspiracies such as QAnon. And, by contextualising QAnon and considering how it could hinder anti-trafficking education, we propose essential approaches to inoculate anti-trafficking messaging from those looking to obscure and co-opt it.

One of the major challenges anti-trafficking educators face is overcoming the myths, misperceptions, and misinformation about human trafficking.[5] For example, the starting point for many QAnon believers is the idea that there is a hidden cabal of elites covering up trafficking and child sexual abuse. Although QAnon welcomes supporters to ‘think for themselves’ and come up with findings they will share through various outlets, such as 8chan/8kun, Facebook, and Twitter, the movement relies on this ‘new’ information to support existing QAnon conspiracies.[6] These conspiracies are quite varied. An analysis of 4,952 Q ‘drops’ (i.e., posts attributed to the ‘real’ Q) showed that Q comments on a variety of topics, and that is reflected in the unstructured nature of QAnon belief.[7] People who have drawn QAnon’s interest include Hillary Clinton, George Soros, Barack Obama, Nancy Pelosi, and Donald Trump. Topics range from Robert Mueller and the Russian collusion investigation to fake news, the Red Cross, Jeffrey Epstein (and his connection to ‘child sex trafficking’), COVID-19, and electoral fraud. This list is not exhaustive, but it does indicate that individuals who may feel a connection to one of these people or topics can be pulled down a proverbial rabbit hole of conspiracy theories. The entry point for QAnon participation, however, is the foundational belief that trafficking and child exploitation are linked to elite power.[8]

Conspiracy theories have long been noted as fundamental to extremism.[9] Extremist beliefs require a clear enemy and absolute opposition as the only available remedy to injustices perpetrated by that enemy. This frame of mind discourages the navigation of differing perspectives required in a pluralistic society, and the dehumanising effects of conspiracy are important for supporting radicalisation. An extensive study by Bartlett and Miller examined the literature, ideology, and propaganda of more than fifty extremist groups from across the political spectrum, including religious, far-right and -left, eco, anarchic, and cult-based, over the past 30 years. They found that every group studied used conspiracy to demonise ‘forces beyond our control, articulating an enemy to hate, sharply dividing the group from the non-group… the frequency of conspiracy theories within all these groups suggests that they play an important social and functional role within extremism itself.’[10] Conspiracy, by definition, can be viewed as instrumental to radicalisation rather than merely as a product of radicalisation. Particularly relevant to anti-trafficking educators is that the zealotry of ‘True Believers’ can inhibit any nuanced attempt to explore the issue seen as deviant from their entrenched perspective.

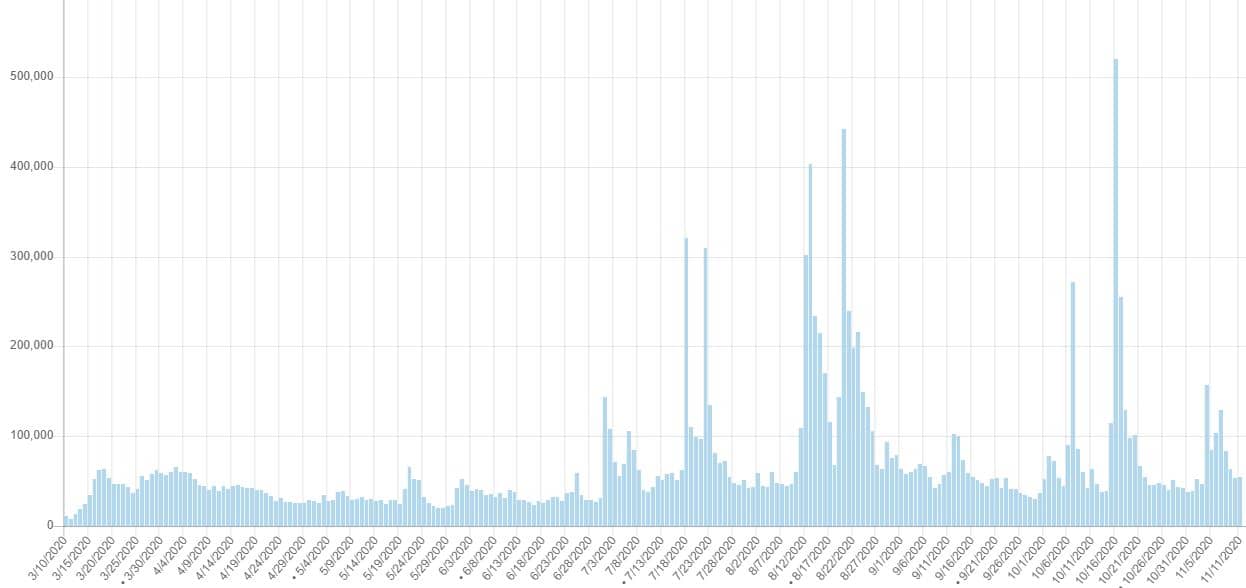

The rhetorical power of conspiracy allowed QAnon to develop from a troubling movement to an embedded cultural force representing a threat to anti-trafficking efforts. The Simon Wiesenthal Center reports that QAnon has gained immense traction, ‘with more than 4.5 million aggregate (social media) followers… one Twitter account monitored… has gained close to 400,000 followers in the past 18 months; it currently has over half a million followers.’[11] From 27 October 2017 to 17 June 2020, a study conducted by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) ‘recorded 69,475,451 million tweets, 487,310 Facebook posts and 281,554 Instagram posts mentioning QAnon-related hashtags and phrases’ inside the United States and across other countries.[12] In the US, as many as 77 Congressional candidates seeking election in November 2020 espoused support for QAnon.[13] This phenomenon is not unique to the U.S., however, as evidenced by the fact that ‘the most popular German-language QAnon YouTube channel, QlobalChange, boasts more than 105,000 subscribers; a similar French-language channel has more than 66,000 and has tripled in less than a month. While Germany and France have the largest movements, there are a significant number of QAnon followers in Italy and the United Kingdom as well.[14] The COVID-19 pandemic, which spurred conspiracies and fear in many places, also appears to have increased interest in QAnon when coupled with online interactions about the 2020 US presidential election. Between March and November 2020, the total Wikipedia pageviews for ‘QAnon’, an indicator of online curiosity about a topic, increased to nearly half a million daily views on peak dates.[15]

Such findings provide evidence that a once marginal conspiracy theory about (child) trafficking has been gaining wide traction on different social media platforms across the globe.

QAnon is composed of a disparate range of conspiracy theories, though trafficking myths remain crucial for believers. While QAnon is a recent movement, anti-trafficking education has long been hindered by disinformation and misinformation that often serves institutional power and allows for co-optation of the concept of trafficking. Within such a context, QAnon uses myths to reify the notion of victimhood and a heroic response from traditional institutional structures. For example, Doezema’s analysis reveals many of the historical myths that would form QAnon.[16] The ‘white slave’ panic in Europe and the United States at the turn of the twentieth century broadly mirrors QAnon as ‘those who fomented the white slavery scare of the time sought to expose precisely the mobile yet highly organized net of the underworld lurking below the surface of society.’[17] The narrative employed by these panics is remarkably similar to the narrative of Q with ‘the procurement, by force, deceit, or drugs, of a white woman or girl against her will, for prostitution’[18] constructed as a massive social problem, despite the number of such cases being very limited. The power of this narrative had sufficient resonance in Europe and the US to produce organisations devoted to its eradication and substantial coverage in the media, along with numerous novels, plays, and films. This panic was extensive enough to have policy implications, with a number of international conferences and legal agreements drafted to stop white slavery.[19]

Implicit within such panics is a notion of lost innocence and virtue that trafficking myths utilise for purposes of removing agency from populations viewed as vulnerable. Such populations are transformed from actors into objects that are acted upon, turning individuals into either victims or potential victims of the constructed narrative of ubiquitous trafficking. The historical context for such views has continued in current trafficking misinformation. Martin and Hill, for example, found that the historical myths of trafficking continue in media coverage and that there is widespread acceptance of such myths.[20] Their work examined the fabricated link between large sporting events and forced sexual exploitation. In looking at media stories linking trafficking and the Super Bowl between 2010 and 2016, they ‘found that 76 per cent of US print media stories reported a causal or correlative link between the Super Bowl and trafficking for sexual exploitation.’[21] The notions of predatory masculinity and the systematic victimisation of exploited and vulnerable women were transformed from myth to fact through the dissemination of the ’Super Bowl sex trafficking’ narrative. Similarly, this myth casts spectators in the role of ‘saviours’ with an imperative to help save ‘victims’. Like the trafficking myths of the past and the current conspiracies of QAnon, media coverage supported this panic:

In 2016, two years before the Minneapolis Super Bowl, an Anti-Sex Trafficking Committee was convened to prepare the region for an anticipated increase in trafficking for sexual exploitation, based on media reporting about previous Super Bowls. The Committee sought support and coordinated efforts with law enforcement, social services (e.g., emergency shelters and street outreach), and volunteer training… with more than 100 representatives from these sectors as well as leaders in business and government, and it raised and spent above one million dollars…[22]

The use of trafficking myths to generate public interest and shape discourse on the subject has long been established in both historical and contemporary contexts. In considering the implications on anti-trafficking education, it is important to establish some of the foundational dynamics enabling such narratives to have pull on public sentiment. These dynamics include the creation of stories that validate traditional power relationships, the construction of trafficking as a cudgel against the Other, and the co-optation of discourse by institutional power.

The role of trafficking narratives as instruments of social cohesion are incredibly consistent. At their foundation is the construction of a pure victim, an evil enemy, and the opportunity for the community to serve as heroic rescuer. The recurring plot casts the spectator in the role of a hero whose awareness and action can stop the omnipresent menace of trafficking. Victimisation is clear and perpetrated by specific bad actors, rather than the product of a broadly unequal system. As Andrijasevic and Mai argue, ‘the mythological function of the trafficking narrative and the victim figure are most visible in the fact that the trafficking plot never varies: it starts with deception, which is followed by coercion into prostitution, moves on to the tragedy of (sexual) slavery and finally finds resolution through the rescue of the victim.’[23]

Supportive media validate the idea of a hero emerging against villains in the trafficking narrative as well. In ‘When the Abyss Looks Back: Treatments of Human Trafficking in Superhero Comic Books’, we examined instances where superhero comic books from 1991 to 2012 made human trafficking an overt plot point. In more than 85 per cent of these stories, the response of superhero characters was violence directed against traffickers who were universally framed as the primary cause of victimisation.[24] Consistent with other media representations, trafficking storylines in comic books present the issue as having a clear causation, simple identification, and swift remedy. As Andrijasevic and Mai note, the outcome of such constructions inevitably benefits neoliberal institutions by preventing structural consideration of inequality while also providing the comfort of a reassuring morality play.

Trafficking narratives, however, frequently have more insidious purposes than just institutional preservation. Historically, human trafficking myths were utilised against marginalised groups, such as migrants, women, working class people, sex workers, and those with stigmatised sexual, racial, or gender identities. Such communities were constructed as a threat to white patriarchal understandings of decency and sexual piety. Whether the threat is built on racialised myths of ‘exotic’ temptations or the Indecent Other exploiting innocents, these constructions ‘reinforce racism and dualistic simplifications of a complex issue.’[25] The invited response is a reifying narrative of rescue where dominant white patriarchal social values can repair the ruptured moral order. Again, this context proves informative in examining the rise of QAnon and how racialised moral panics about trafficking have found traction in both mainstream and social media.

Novel use of media has and continues to support such trafficking panics. The 1913 film Traffic in Souls was a fictionalised depiction of white women trafficked into sexual economies in New York City.[26] At the turn of the twentieth century, the lurid subject matter offered prurient appeal to audiences of the time with innovative cinematic techniques that made the film an artistic landmark. Viewed as a technical masterpiece, Traffic in Souls reflected what was seen as a national moral imperative to protect innocent white women from the dangers of racialised urban spaces. As the Travellers’ Aid Society noted, ‘Every year, thousands of young women come to the great cities looking for a chance of honourable livelihood. Rich in hope and ambition but lacking in experience and resource, they fall easy prey to the evil that is always lying in wait for the unprotected woman at the Terminals and Docks.’[27] A similar media furore accompanied the release of D.W. Griffith’s racist film Birth of a Nation in 1915. Writing about the implications of the film (which had a similar level of technical achievement as Traffic in Souls, Obasogie calls it an ‘epic celebrating the Ku Klux Klan’s rise during Reconstruction to defend Southern whites’ dignity and honour against what were then seen as recently liberated Black insurgents.’[28] What is important to note in relation to QAnon is both the exigence the film constructs and its corresponding response. Specifically, the turning point in Birth of a Nation occurs when formerly enslaved people are constructed as a menace organising the abduction and sexual assault of a white woman. The Ku Klux Klan is presented as heroically stopping this menace and the film was so powerful that it is credited with creating a second rise of the KKK in that era. Similar to Traffic in Souls and Birth of a Nation, QAnon conspiracies utilise novel media techniques to generate a public response to imagined threats. In the case of QAnon, that includes exploitation of new media such as social channels and video sharing sites. While less explicit than these historical films, the construction of a threat to the traditional moral order remains, although it is more coded and not tied to only one racialised threat. Paranoia about LGBTQ+ rights, perceptions of politically radical enemies, and fears about losing a privileged white status permeate the ideology of many Q believers.[29]

However, one overt target of conspiracy theory, now and in the past, are Jewish people. The QAnon movement promotes a belief in a Jewish-controlled cabal of global trafficking operations.[30] The linkage between trafficking myths and dissonance about pluralism has been present historically in antisemitic representations of trafficking panics. Antisemitic trafficking tropes date back to the Middle Ages and have persisted in the centuries since then. Early conspiracies ‘alleged that Jews were responsible for kidnapping Christian children and drinking their blood for religious rituals. Those claims, called blood-libel conspiracy theories, persisted throughout the 1800s and into the 20th century.’[31] The persistence of such myths can be found in QAnon messaging, with prominent Jewish politicians, entertainers, and business people frequently singled out as ringleaders in the abduction and exploitation of children. While Q followers may not be aware of the genealogies of these conspiracies, both the hatred they inspire and the target of that hatred remain in place. The motivations that inspired violent attacks against Jewish immigrant communities in centuries past are forebears to the frequent death threats levied against individuals like George Soros (a major Q target) and broader ongoing violence against Jews.[32]

This tendency to co-opt and manipulate issues of concern to support racist and reactionary social positions has been noted as both a contemporary and historical tactic. In previous studies, we used the concept of ‘hatejacking’[33] to describe when an extremist group claims the discursive space around a topic. In such instances, extremist groups have tended to latch onto issues of concern to gain legitimacy and recruit support from people who would otherwise be unlikely to adopt such extremist views. This sort of co-optation is described by Ganesh and Zoller as ‘a tactic of power’[34] that frequently allows dominant groups to solidify institutional support through the repackaging of reactionary messaging. In the case of QAnon, people who would not necessarily be drawn to conspiratorial worldviews are brought in by the benevolent sounding messages of ‘saving the children’ or ‘stopping the traffickers’. Particularly challenging for anti-trafficking educators is the fact that such ‘hatejacks’ frequently make rebuttal and response to these positions difficult, as responding to these conspiracies can have the effect of giving the conspiracy the illusion of legitimacy. Cumulatively, the context, dissemination, and presentation of trafficking myths have allowed QAnon to flourish in trafficking discourse, making anti-trafficking education all the more difficult.

While QAnon includes a broad range of conspiracy theories,[35] its essential element focuses on the abduction and trafficking of children. As noted, the construction of trafficking in QAnon discourse mirrors many of the most common myths anti-trafficking education seeks to remedy. These include the common misunderstanding that human trafficking is limited to the sex industry, disregarding the many different forms of exploitation, including labour trafficking, organ trafficking, the use of child soldiers, or the practice of child marriage.[36] This emphasis is not unexpected when QAnon is contextualised, at core, as a movement that seeks to reinforce racialised and gendered roles of feminine helplessness and protection by traditional (i.e., masculine) institutions. Mahdavi and Sargent view such a construction as a conflation of ‘womenandchildren’ as a singular, vulnerable group without agency. This paradigm excludes ‘men and women who violate gender boundaries of passivity (from) accessing the trafficking discourse in order to include their narratives as legitimate experiences within the current framework.’[37] The exigence for rescue is further established with iconography suggesting that ‘womenandchildren’ are imprisoned and in peril. Fukushima writes extensively on the ‘cage imagery’ used in anti-trafficking discourses that reinforces a narrative of universal victimhood and the annihilation of ‘victim’ autonomy.[38] Cage imagery has been used as a trafficking metaphor in education and awareness-raising materials, through government initiatives, by NGOs, and even by ostensibly feminist organisations. While QAnon’s construction of a vast network of imprisoned and helpless victims appears far-fetched, it is an extension of myths perpetuated in anti-trafficking discourses.

The ‘womenandchildren’ conflation is exclusionary and contains inaccuracies that anti-trafficking education should seek to remedy. Boys and men, for example, are equally likely to be trafficked, albeit commonly for different forms of exploitation.[39] Additionally, most human trafficking victims are not kidnapped, contrary to many of the trafficking scares spun by QAnon supporters: the vast majority of trafficking victims are exploited by means of deception, fraud, and force, and some through familial or romantic relationships.[40] QAnon similarly precludes the possibility of the autonomy of at-risk populations with the ‘victim’ label assumed even in cases where participation in labour such as sex work may be consensual.[41] It is important to note, though, that the historical ‘white slavery’ myths are not simply reproduced in the present. As Hua and Nigorizawa note, the legal and cultural distinction between victim and criminal in the construction of human trafficking has increasingly been focused on the market position of the individual. They state that ‘the dichotomizing of sex trafficking victim against sex worker assumes that consent can be easily identified and assumes the categories are mutually exclusive—the logic follows “once a prostitute, always a prostitute”. Hence, anti-trafficking laws work within “a system that celebrates the mobility of capital and some bodies [victims], while the bodies of others [undocumented immigrants and sex workers] face ever-growing restrictions and criminalization”.’[42] A paradoxical bind, therefore, now exists, whereby loss of capital makes one a victim and the acquisition of capital makes another an offender. In this narrative space, there is no room for nuance or agency; only pure victims, evil villains, and heroic protectors.

Aside from the connection to known myths, QAnon’s structure (or non-structure) appears to invite even more unique and bizarre mythologising from its followers. Among these is the unsubstantiated claim that the furniture store Wayfair is running a child trafficking ring and names furniture pieces with the names of real child trafficking victims for sale. Another shared rumour cautions people to be suspicious of white passenger or commercial vans with external locks as a sign of possible trafficking activity.[43] Almost by design, the absurdity of these claims makes reasoned responses seem fruitless. Sincere and informed anti-trafficking education can engage with audiences on challenging, critical questions about the causes, experiences, and effects of trafficking. It is not now equipped, however, to respond to outlandish memes that are wholly divorced from reality. Despite being divorced from it, QAnon conspiracies are, nevertheless, affecting reality.

An analysis of Google search results for ‘QAnon crime’ found sixteen cases between December 2016 and October 2020, in which the perpetrators committed actual criminal acts, motivated by QAnon conspiracies. Among the crimes committed were kidnappings related to custody issues, weapons offenses, assault, murder, arson, and terrorism. In one case, the perpetrator(s) threatened Democratic State Senator Scott Wiener with decapitation for his controversial support of California Senate Bill No. 145, which eliminated automatic sex offender registration for young adults who have anal or oral sex with a minor.[44] So far, no arrests have been made in this case. Such examples are by no means to be considered representative or comprehensive, but they do show how some people transform conspiracy theory into practice.

Taken together, historical trafficking myths provide a substantial foundation for understanding the prevalence and flexibility of QAnon. With that in mind, it is imperative to consider the ways that anti-trafficking education efforts are prepared (or unprepared) to counter conspiracy theory. An important first step in that preparation is to acknowledge the degree to which people participating in anti-trafficking courses, outreach events, and other educational activities arrive with preconceptions that may be informed by current and ongoing trafficking myths. The residual effects of historical myths and their current iterations could well serve as a lens for participation or even be what draws people to participate in the anti-trafficking event in the first place. Some participants in educational events primed with misinformation require a developed and informed exploration of the issue of trafficking, lest the easy answers and evil villains provided by narratives such as QAnon dominate their overall thinking about anti-trafficking.

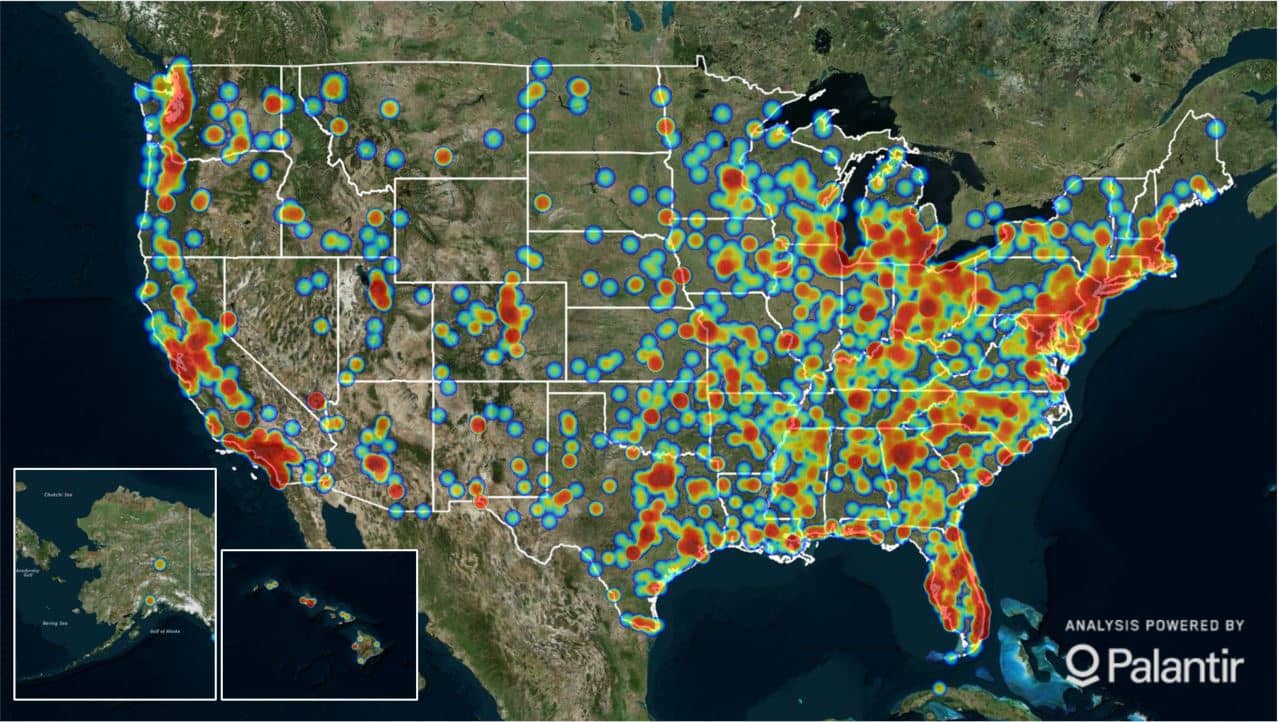

Additionally, the well-intentioned efforts of participants in anti-trafficking educational forums and courses may be entrenching these perspectives. The process of stigmatising immigrant labour and circumstances under the guise of creating communities in need of rescue can further the paternalistic construction of trafficking. Sharma argues that ‘such campaigns within the global North, often led by feminists, constitute the moral reform arm of contemporary anti-immigrant politics that targets negatively racialized migrants.’[45] The complicity of ostensibly anti-trafficking advocacy in furthering this perspective is salient and concerning. As noted in the previous discussion of QAnon, these narratives do not exist merely in the heads of believers. They constitute a threat of action. Shih’s ethnographic work on the San Francisco-based anti-trafficking non-profit Not for Sale’s campaign of ‘backyard abolitionism’ is particularly chilling. She describes the group’s renegade effort to end ‘modern-day slavery’ with actions taken against sites the group perceived as ‘trafficking hubs’, frequently based on rumour, misinformation, and dubious ‘tips’ received. More broadly, Shih argues this effort is part of a movement ‘away from a model of mere “partnerships” between state and nonstate actors’ and that ‘the rise of civilian vigilantism over the past decade may be attributed to the framing of social concerns as exceptional and seemingly outside of law enforcement’s control.’[46] An increased militancy by some members of the anti-trafficking movement is frequently informed by ‘awareness raising’ messaging. Polaris’ ‘Heatmap’ of trafficking cases, for example, creates the impression of an omnipresent trafficking threat as well as certain hotspots that should be targeted.

It is imperative that educators in the field of anti-trafficking directly engage and counter the narratives perpetuated by the QAnon movement and critically reflect on how these conspiracies exclude and preclude consideration of the real issues that require understanding in relation to human trafficking. As Gerasimov notes, ‘[QAnon conspiracies] can lead to not only a misunderstanding of the issue, but also a wrong response… If you portray human trafficking as something that a secret cabal is doing, the solution becomes guns and surveillance. This is totally not the solution to trafficking. … The solutions that anti-trafficking groups advocate for … are about improving social programs so kids don’t fall through the cracks and end up in situations that leave them vulnerable to exploitation.”[47] By understanding the cleavage between the human trafficking information being shared and the accuracy of that information, the challenges of navigating anti-trafficking in the age of Q can be more clearly defined and addressed.

To that end, we explored an important space of anti-trafficking education: university courses on the subject. Specifically, we reviewed course syllabi that were publicly available online. We looked for syllabi of courses with a focus on deconstructing trafficking myths and that invite reflection on how the presentation of trafficking is frequently at odds with its reality. Such an approach, from the perspective of this research, would uniquely position the course to interrogate the historical and ongoing misinformation that is a foundation of QAnon belief. The acquisition of these syllabi was made through a Google search for ‘trafficking course syllabus’ and ‘university’. We reviewed a total of sixteen syllabi from 2017 to 2021 (roughly the time period of the emergence of QAnon) from courses at universities throughout the world. This is not a comprehensive analysis of these documents or university anti-trafficking education more broadly, but this search did provide some compelling examples and conceptual work. For example, one syllabus noted:

…the white slavery hysteria was not only about prostitution. It also provided activists with a way to express anxieties about other cultural shifts, including, but not limited to: women’s increased employment, urbanization, immigration, internal migration, new forms of recreation, shifting gender norms, and changing sexual mores… the contemporary campaigns against sex trafficking bring together strange alliances as feminist organizations coordinate with Christian evangelicals to raise awareness of the issue. Sex workers’ rights activists also contribute their voices to the current conversation about sex trafficking, drawing attention to the ways that ‘victims’ of sex trafficking are frequently rendered mute by the anti-trafficking activists who claim to be fighting on their behalf.

Another syllabus used a case specific approach to evaluate myths related to trafficking:

Before the World Cup held in Brazil in Summer 2014, many fans saw billboard posters and social media ads featuring the silhouette of a naked woman standing on a playing field, her feet clad in red high heels with chains shackled to her ankles. The ad was promoted by an anti-trafficking organization claiming sporting events like the World Cup become periodic ‘hot spots’ for sex trafficking and exploitation, as millions of fans, athletes, and affiliated sponsors flock to major cities. However, the ad was met with protest from a number of organizations, especially sex workers’ rights organizations, that such publicity merely increased policing and police brutality around the event, and no increase in trafficking was actually reported.

Myth deconstruction also benefits from a nuanced exploration of trafficking. An examined syllabus noted:

Our case examples will include issues that receive high media publicity—forced sex work, child labour in construction and clothing, and the illicit trade in organs—but also pay attention to ‘less sexy’ forms of trafficking and exploitation. These include exploitation and sexual violence in strawberry fields and American beef farms, debt bondage in Thai shrimp processing plants, abuses of Bangladeshi construction workers and Filipina domestic workers in the Gulf region, smuggling and exploitation after major natural disasters and post-war conflicts, and the exploitation of Dominican baseball players and Siberian fashion models alike.

Particularly outstanding in this sample text is the fact that it makes clear that sexual exploitation needs to be contextualised as part of broader exploitation. Similarly, in other syllabi, sample text included statements such as the following:

Individuals are trafficked for numerous reasons and purposes, including for prostitution, domestic or agricultural labour, or exploitation in any number of commercial activities. The common thread is the reduction of the trafficked human being to a mere commodity, generating profits for his/her trafficker.

These sorts of statements and perspectives can help learners to understand and contextualise human trafficking, rather than being pulled in the direction of misinformation and myths. Moving the topics and themes of anti-trafficking education away from myths is crucial; however, media literacy must now be prominently placed in any anti-trafficking education as well. Media theorist Adrian Ivakhiv notes that QAnon calls upon people to do ‘do their own research.’[48] This would be consistent with the orthodoxy of media literacy as checking sources and evaluating evidence facilitates critical consumption of information, which is an overt goal of media literacy education. In the case of QAnon, however, ‘research’ takes on a different character where people are encouraged to evaluate selected data through a conspiratorial lens. Ivakhiv argues that ‘with QAnon, it turns out, research is the connect-the-dots activity that keeps followers engaged in the movement.’ What appears to be critical information evaluation actually serves as a process of conspiracy confirmation where biases are groomed and subsequent information is contextualised as support of the bias. Anti-trafficking education should also assist learners in evaluating the trafficking-related sources and information they come across. Doing so can help to identify the sorts of clicks, views, and shares that can pull users down the proverbial rabbit hole.

As noted, the QAnon conspiracy theory is pervasive, with extensive traction online. The misinformation is so extensive that tech companies have had to adjust their policies and algorithms in an attempt to slow the extent of QAnon content being shared.[49] For anti-trafficking educators, this presents the very real possibility of Q-inclined students and audience members co-opting discussions of trafficking with conspiracies and propaganda. There is also a chance that well-intentioned educational content will be recontextualised and manipulated by audiences primed to believe the misinformation of Q and the historic trafficking myths QAnon is aligned with. While daunting, this research suggests that there are approaches to mitigate against myths and conspiracies and to ensure that educational outreach remains focused on accuracy and authenticity.

Broadly, anti-trafficking educators need to have an action plan prepared for engaging with learners trying to pivot sessions toward Q-related conspiracies. As suggested by existing scholarship, a starting point could be to ensure that a discussion of ‘myth versus reality’ is undertaken early on in any communication about human trafficking. By presenting popular and conspiratorial misperceptions of trafficking, educators can defuse potentially disruptive content from overwhelming the discussion. As noted, most QAnon conspiracy theories are localised to generate maximum fear and spread, such as the examples of shadowy ‘trafficking vehicles’ menacing neighbourhoods. Trafficking is a global phenomenon and by emphasising its broader dimensions, the sensationalised (and often fictional) local incidents can be placed in a more realistic context. Finally, by providing information from reputable outlets (such as credible NGOs), the discussion can be grounded in evidence rather than speculative and constructed mythical narratives. This research suggests teaching a systemic view of exploitation as opposed to one based on the individualised heroes and villains that populate trafficking myths.

At base, anti-trafficking education seeking to counter misinformation and disinformation must acknowledge the existence of misinformation and disinformation. There is precedent for such an approach being successful. When Martin and Hill worked to educate local media about the ‘Super Bowl sex trafficking’ myth, their data-informed approach directly countered this narrative and produced results. In analysing subsequent media coverage, they found a 46 per cent decrease in media reporting on a link between trafficking and sporting events along with ‘less sensationalist language and fewer inflated numbers compared to previous coverage.’[50]

The phenomenon of QAnon is emergent, but the myths it promotes are not new. Anti-trafficking education must engage with these myths and conspiracies or risk co-optation and contributing to them. While the current prevalence of QAnon presents a challenge for anti-trafficking advocacy and education, pedagogical approaches that critically assess the racialised and gendered myths long prevalent in public discourses about trafficking are well suited to actively combat conspiracy theory.

Bond Benton is an Associate Professor of Public Relations at Montclair State University. He obtained his doctorate from the University of Vienna, with his dissertation focusing on the influence of culture on meaning. A particular focus of Dr Benton’s research is the interaction of media, branding, and cross-cultural communication as it relates to the values and decisions of constituencies. Dr Benton’s essays and research articles have appeared in journals and anthologies including The Journal of E-Learning and Digital Media, Public Relations Tactics, Cases in Public Relations Strategy, The Journal of Popular Culture, The Journal of Applied Security Studies, and Studies in Communication Sciences. He is the author o the book, The Challenge of Working for Americans: Perspectives of an international workforce (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). Dr Benton also works on the communication team of the Global Center on Human Trafficking at Montclair State University. Email: bentonb@montclair.edu

Daniela Peterka-Benton is an Associate Professor of Justice Studies at Montclair State University. She obtained her doctorate in Sociology, with a specialisation in Criminology from the University of Vienna. Her research interests centre around transnational crimes such as human trafficking, human smuggling, arms trafficking, and right-wing terrorism and extremism. Dr Peterka-Benton has published numerous articles in journals including International Migration Review, The Journal of the Institute of Justice & International Studies, and The Journal of Applied Security Research, and is currently working on a human trafficking data analysis grant with the New Jersey Division of Criminal Justice. Prior to her focusing on a full-time academic career, Dr Peterka-Benton worked for the US State Department’s Office of Diplomatic Security at the US Embassy in Vienna, Austria. Dr Peterka-Benton also holds leadership positions in Education, Training and Grants for the Global Center on Human Trafficking at Montclair State University. Email: peterkabentd@montclair.edu

[1] A Gallagher, J Davey, and M Hart, ‘The Genesis of a Conspiracy Theory: Key trends in QAnon activity since 2017’, Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 2020, retrieved 3 January 2021, https://www.isdglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/The-Genesis-of-a-Conspiracy-Theory.pdf.

[2] T C Lehmann and S A Tyson, ‘Sowing the Seeds: Radicalization as a political tool’, American Journal of Political Science, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12602.

[3] FBI Phoenix Field Office, ‘Anti-Government, Identity Based, and Fringe Political Conspiracy Theories Very Likely Motivate Some Domestic Extremists to Commit Criminal, Sometimes Violent Activity’, Federal Bureau of Investigation Intelligence Bulletin, 30 May 2019, https://info.publicintelligence.net/FBI-ConspiracyTheoryDomesticExtremism.pdf.

[4] J Cook, ‘“It’s Out of Control”: How QAnon undermines legitimate anti-trafficking trafficking efforts’, Huffington Post, 14 September 2020, retrieved 25 September 2020, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/how-qanon-impedes-legitimate-anti-trafficking-groups_n_5f4eacb9c5b69eb5c03592d1.

[5] R Andrijasevic and N Mai, ‘Trafficking (in) Representations: Understanding the recurring appeal of victimhood and slavery in neoliberal times’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 7, 2016, pp. 1–10, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121771; J Doezema, ‘Loose Women or Lost Women? The re-emergence of the myth of white slavery in contemporary discourses of trafficking in women’, Gender Issues, vol. 18, 1999, pp. 23–50, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-999-0021-9.

[6] A J Ivakhiv, ‘“Do Your Own Research”: Conspiracy practice as media virus’, Immanence: Ecoculture, Geophilosophy, Mediapolitics, University of Vermont Blogs, 5 January 2021, https://blog.uvm.edu/aivakhiv/2021/01/05/do-your-own-research-conspiracy-practice-as-media-virus.

[7] E Tian, ‘The QAnon Timeline: Four years, 5,000 drops and countless failed prophecies’, Bell¿ngcat, 29 January 2021, https://www.bellingcat.com/news/americas/2021/01/29/the-qanon-timeline.

[8] A W Goldenberg et al., The QAnon Conspiracy: Destroying families, dividing communities, undermining democracy, Network Contagion Research Institute, 15 December 2021, https://networkcontagion.us/wp-content/uploads/NCRI-%E2%80%93-The-QAnon-Conspiracy-FINAL.pdf.

[9] M Barkun, ‘Religion, Militias and Oklahoma City: The mind of conspiratorialists’, Terrorism and Political Violence, vol. 8, issue 1, 1996, pp. 50–64, https://doi.org/10.1080/09546559608427332; N James, ‘Militias, the Patriot Movement, and the Internet: The ideology of conspiracism’, The Sociological Review, vol. 48, issue 2_suppl, 2000, pp. 63–92, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2000.tb03521.x.

[10] J Bartlett and C Miller, The Power of Unreason Conspiracy Theories, Extremism and Counter-Terrorism, Demos, London, 27 August 2010, https://demosuk.wpengine.com/files/Conspiracy_theories_paper.pdf.

[11] Simon Wiesenthal Center, QAnon: From fringe conspiracy to mainstream politics, Simon Wiesenthal Center, 22 September 2020, https://www.wiesenthal.com/assets/qanon-from-fringe-conspiracy.pdf.

[12] Gallagher, Davey, and Hart.

[13] ‘Red, White, and Q: QAnon candidates move forward in U.S. elections’, The Soufan Center, 26 August 2020, https://thesoufancenter.org/intelbrief-red-white-and-q-qanon-candidates-move-forward-in-u-s-elections.

[14] J Keating, ‘How QAnon Went Global’, Slate Magazine, 8 September 2020, https://slate.com/technology/2020/09/qanon-europe-germany-lockdown-protests.html.

[15] ‘Wikipedia Trends.’ n.d., retrieved 20 September 2020, https://www.wikishark.com.

[16] Doezema.

[17] E Olund, ‘Traffic in Souls: The ‘new woman,’ whiteness and mobile self-possession’, cultural geographies, vol. 16, issue 4, 2009, pp. 485–504, https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474009340088.

[18] Ibid., p. 25.

[19] J Allain, ‘White Slave Traffic in International Law’, Journal of Trafficking and Human Exploitation, vol. 1, issue 1, 2017, pp. 1–40, https://doi.org/10.7590/24522775111.

[20] L Martin and A Hill, ‘Debunking the Myth of “Super Bowl Sex Trafficking”: Media hype or evidenced-based coverage’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 13, 2019, pp. 13–29, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201219132.

[21] Ibid., p. 14.

[22] Ibid., p. 16.

[23] Andrijasevic and Mai, p. 3.

[24] B Benton and D Peterka-Benton, ‘When the Abyss Looks Back: Treatments of human trafficking in superhero comic books’, Popular Culture Studies Journal, vol. 1, issue 1-2, 2013, pp. 18–35, https://mpcaaca.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/PCSJ-V1-N12-Benton-Benton-When-the-Abyss-Looks-Bac1.pdf.

[25] M Desyllas, ‘A Critique of the Global Trafficking Discourse and U.S. Policy’, The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, vol. 34, issue 4, 2007, pp. 57–-80, https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol34/iss4/4.

[26] Olund.

[27] ‘Facts Everyone Should Know’, Travelers’ Aid Society, ca. 1913, p. 3.

[28] O K Obasogie, ‘The Rebirth of a Nation? Glorifying eugenics in a cult classic for our times’, Colorlines, 3 October 2007, retrieved 26 July 2021, https://www.colorlines.com/articles/rebirth-nation.

[29] S Wiener, ‘What I Learned When QAnon Came for Me’, The New York Times, 19 October 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/19/opinion/scott-wiener-qanon.html.

[30] G Stanton, ‘QAnon Is a Nazi Cult, Rebranded’, Just Security, 9 September 2020, https://www.justsecurity.org/72339/qanon-is-a-nazi-cult-rebranded.

[31] R E Greenspan, ‘QAnon Builds on Centuries of Anti-Semitic Conspiracy Theories’, Insider, 24 October 2020, retrieved 31 December 2020, https://www.insider.com/qanon-conspiracy-theory-anti-semitism-jewish-racist-believe-save-children-2020-10.

[32] S Burley, ‘Soros, “Cultural Marxism” and QAnon: How the GOP is energizing and entrenching antisemitism in America’, Haaretz, 24 February 2021, https://www.haaretz.com/us-news/.premium-how-the-gop-is-energizing-and-entrenching-antisemitism-in-america-1.9560897; I Fattal, ‘A Brief History of Anti-Semitic Violence in America’, The Atlantic, 28 October 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/10/brief-history-anti-semitic-violence-america/574228.

[33] B Benton and D Peterka-Benton, ‘Hating in Plain Sight: The hatejacking of brands by extremist groups’, Public Relations Inquiry, vol. 9, issue 1, 2020, pp. 7–26, https://doi.org/10.1177/2046147X19863838.

[34] S Ganesh and H M Zoller, ‘Dialogue, Activism, and Democratic Social Change’, Communication Theory, vol. 22, issue 1, 2012, pp. 66-91, p. 74, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2011.01396.x.

[35] M Spring and M Wendling, ‘How COVID-19 Myths Are Merging with the QAnon Conspiracy Theory’, BBC News, 2 September 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-53997203.

[36] Blue Campaign, ‘Myths and Misconceptions’, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, retrieved 23 October 2020, https://www.dhs.gov/blue-campaign/myths-and-misconceptions.

[37] P Mahdavi and C Sargent, ‘Questioning the Discursive Construction of Trafficking and Forced Labour in the United Arab Emirates’, Journal of Middle East Women's Studies, vol. 7, issue 3, 2011, pp. 6–35, https://doi.org/10.2979/jmiddeastwomstud.7.3.6.

[38] A I Fukushima, ‘Anti-Violence Iconographies of the Cage: Diasporan crossings and the (un)tethering of subjectivities’, Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 36, issue 3, 2015, pp. 160–192, https://doi.org/10.5250/fronjwomestud.36.3.0160.

[39] ‘Child Trafficking: Myth vs. Fact’, Save the Children, retrieved 23 October 2020, https://www.savethechildren.org/us/charity-stories/child-trafficking-myths-vs-facts.

[40] M Brown, ‘Do Traffickers Kidnap Their Victims? The myths and realities of human trafficking’, The Fuller Project, 25 February 2019, https://fullerproject.org/story/do-traffickers-kidnap-their-victims-the-myths-and-realities-of-human-trafficking.

[41] Doezema.

[42] J Hua and H Nigorizawa, ‘US Sex Trafficking, Women’s Human Rights and the Politics of Representation’, International Feminist Journal of Politics, vol. 12, issue 3-4, 2010, pp. 401–423, p. 407, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2010.513109.

[43] ‘Human Trafficking Rumors’, Polaris Project, retrieved 23 October 2020, https://polarisproject.org/human-trafficking-rumors.

[44] R Myrow, ‘QAnon Followers Attack SF’s Scott Wiener Over Sex Offender Law’, KQED, 15 September 2020, https://www.kqed.org/news/11837862/qanon-followers-attack-sfs-scott-wiener-over-sex-offender-law.

[45] N Sharma, ‘Anti-Trafficking Rhetoric and the Making of a Global Apartheid’, National Women's Studies Association Journal, vol. 17, issue 3, 2005, pp. 88–111, https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/189422.

[46] E Shih, ‘Not in My “Backyard Abolitionism”: Vigilante rescue against American sex trafficking’, Sociological Perspectives, vol. 59, issue 1, 2016, pp. 66–90, p. 71, https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121416628551.

[47] K Rogers, ‘Trump Said QAnon “Fights” Pedophilia. But the group has made it harder to protect kids’, FiveThirtyEight, 15 October 2020, https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/qanons-obsession-with-savethechildren-is-making-it-harder-to-save-kids-from-traffickers.

[48] Ivakhiv.

[49] J Guynn, ‘Facebook Cracks down on QAnon for Hijacking Save the Children Movement’, USA Today, 30 September 2020, https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2020/09/30/facebook-cracks-down-qanon-save-children-trump/5875372002.

[50] Martin and Hill, p. 26.