ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

Annjanette Ramiro Alejano-Steele

For university instructors who teach human trafficking as a comprehensive course, design decisions often begin with determining scope, disciplinary orientation, and learning goals. Further decisions involve pedagogical approaches and how to best support and sustain student learning. With civic engagement principles, universities can situate themselves within local anti-trafficking initiatives by offering courses to expand organisational capacities to end human trafficking. Using Human Trafficking 4160 at Metropolitan State University of Denver as an example, this paper provides key design questions to create a civically-engaged multidisciplinary course, partnered with agencies statewide, and equipped to support students primed for social justice and systems change. It offers suggestions for community partnerships to deliver content and co-create learning activities. It also provides pedagogical techniques to facilitate inclusive, trauma-informed learning spaces.

Keywords: human trafficking, civically engaged pedagogy, social justice pedagogy, trauma-informed teaching

Please cite this article as: A R Alejano-Steele, ‘Civically Engaged and Inclusive Pedagogy: Facilitating a multidisciplinary course on human trafficking’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 17, 2021, pp. 91-112, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201221176.

My hope emerges from those places of struggle where I witness individuals positively transforming their lives and the world around them. Educating is always a vocation rooted in hopefulness.[1]

The teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach. They become jointly responsible for a process in which all grow.[2]

The year 2000 marked a time of global and national significance in the fight to name, define, and address human trafficking. As definitions emerged from a transnational organised crime perspective, universities—known for their roles as knowledge producers and disseminators— worked to advance language and descriptions of human trafficking and amplify public awareness. The early offerings of definition-focused content began as single lectures on global human trafficking, situated within larger courses in international studies graduate programmes and law schools.[3] At that time, course content focused on global and national definitions, funding sources, and emerging laws that shaped anti-trafficking responses. Far less attention was given to content delivery or attention to trauma-informed, multidisciplinary and inclusive pedagogies to support student learning. Based on offering Human Trafficking 4160 for more than thirteen years and teaching nearly 675 students, in this paper, I present key course design considerations, using a civic engagement perspective in order to bridge theory and practice. I also offer course design questions to build a multidisciplinary course with social justice facilitation tools to deliver content. Course design begins by first considering university support systems in place for community partnerships, disciplinary bias of instructors, geographic scope of course coverage, and historical context to guide operational definitions and frameworks.

Universities[4] with civic engagement orientations conduct their academic work in partnership with community sectors and agencies—among them social services, government and business sectors, community foundations, and non-profit community organisations. Together, universities and their partners share authority in the co-creation of knowledge to address societal issues, and value democratic participation as a central purpose of higher education.[5] In the early 2000s, many universities reframed their missions to provide education and support to communities, building on the women’s and civil rights movements that demanded diversity and inclusion in higher education.[6] Since then, hundreds of institutions have seen increases in student civic participation, student retention, and dedication to social change issues.[7] In the United States, the Association of American Colleges & Universities has noted the value of civic engagement as providing ‘high-impact learning opportunities that engage student(s) in solving unscripted, real-world problems across all types of institutions, within the context of the workforce, not apart from it.’ [8] As universities grapple with student retention during the COVID-19 pandemic, civic engagement approaches are more relevant than ever.

Many civically engaged universities have institutional structures to sustain community partnerships (e.g., internship and career centres), and have evaluation structures that value publicly engaged faculty who serve as academic stewards of change. Driven by a commitment to creating socially just and equitable societies, publicly engaged faculty honour the transdisciplinary nature of knowledge that is co-created in and with community[9] as they support students in the hope that they will become community leaders. Further, many publicly engaged scholars can facilitate ‘third space’[10] classrooms as conceptualised by bell hooks and Paulo Freire. Third space facilitators address community problems, using pedagogical tools that validate student identities, community knowledge, and resilience as essential to effective teaching and learning.[11] As a result, students graduate with greater sensitivity to community needs, having gained hands-on experience and empathy. How different universities offer students civic engagement experience varies widely; an example highlights the combination of curriculum and high-impact teaching practices.

Metropolitan State University of Denver (MSU Denver) was established in 1965, and is federally designated as a Hispanic-serving urban institution. MSU Denver’s mission is to provide high-quality, accessible education with steadfast commitment to serving diverse communities. Its modified open-admissions policies have afforded education to those who would not otherwise gain access, spanning a range of socioeconomic backgrounds, race and ethnic groups, disability, and military veteran and citizenship status, among others. Forty-eight per cent of students are from a low-income background; forty per cent are non-traditional (age 25 or older); fifty-six per cent are first-generation students; and eighty per cent are working adults. Contrary to stereotypes about ‘at-risk and underserved’ student populations, MSU Denver students are living proof of perseverance and resilience.

The university’s reputation and mission are the direct result of carefully cultivated partnerships with a range of community sectors and agencies. Together, scholarly inquiry and knowledge is co-created to combine classroom experience with community-based service on issues that, for example, affect undocumented communities, individuals experiencing homelessness, and migrant workers. Examples of MSU Denver accolades for civic engagement work have included fire and injury prevention education to refugees and immigrants; practical experience gained through working with adults with major mental illnesses; and study abroad opportunities to develop humanitarian engineering innovations (e.g., pulse jets or water filtration systems) with community leaders in other countries.[12] MSU Denver’s civically engaged faculty empower students to advance social change with the tenet of education as freedom, and third space classrooms invite students to discuss tensions between lived experiences and theory. For example, first generation students and undocumented students make sense of their community in the context of broader social, political, and economic forces,[13] developing greater understanding of their precarity for exploitation broadly, and human trafficking specifically. MSU Denver’s civic engagement orientation and students’ lived experiences anchored the design of Human Trafficking 4160, honing its focus upon Colorado.

My background as a dually-tenured professor in Psychology and Gender Studies at MSU Denver began with disciplinary training as health psychologist whose community-based work focused on underserved women and social determinants of health in the areas of pregnancy, stress, and violence. My disciplinary biases frame how I see the development and well-being of humans within societal structures, and I have brought these lenses to my work in the anti-trafficking field over the last sixteen years. In addition to my work on campus, I am also the co-founder of the Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking (LCHT), a non-profit separate from the university that has provided education, community-based research, and the statewide anti-trafficking hotline and textline since 2005. I co-designed the course with my co-founder Amanda Finger, other LCHT staff, and the added input of community practitioners[14] with a flexible range of topics that reflect the ever-evolving community response. Within MSU Denver, eight cross-listed departments engaged in discussion and formal curriculum review to ensure that learning objectives met disciplinary programme needs.

HT 4160 is facilitated by instructors and guest lecturers with years of practical experience in the anti-trafficking field. Together, they blend multidisciplinary theories and frameworks with field applications to illustrate the complexities of anti-trafficking responses across Colorado. Civic engagement opportunities deepen student learning, providing hands-on experience as individuals or in groups. The course’s cross-listed design mirrors comprehensive community responses to human trafficking specifically, within a context of human rights advances in Colorado. Course delivery has also been integrated with both student support services and broader Colorado anti-trafficking resources. Over the last 14 years, all six of HT 4160’s instructors have been affiliated with LCHT, including survivors, co-founders, board members, and staff. This collaborative civic engagement design ensures connection to current statewide anti-trafficking efforts, and further guarantees that community voices, collaborations, and resources remain central to the course.

Historical and geographic context has directed how HT 4160’s content has evolved over the years; its design was driven by the needs of students, community systems, and local anti-trafficking initiatives. As course design developed in 2006, many US states like Colorado were developing coordinated responses to human trafficking in the wake of the adoption in 2000 of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA). US policies shaped state-level responses through funding. The Bush administration set its Department of Justice funding priorities upon training law enforcement and catalysing faith-based organisations to coordinate service provision. Early funding also prioritised support for victims of trafficking in the sex industry, excluding people trafficked in the formal economy.

Colorado’s human trafficking efforts were amongst the first to benefit from federal funding for protection and prosecution; funding also supported prevention outreach to ‘at-risk’ communities (e.g., detention centres, migrant farm workers, or youth experiencing homelessness). The response protocols encompassed all forms of human trafficking with added requirements to partners, thus coordinating a variety of actors, among them, law enforcement, local community agencies, and faith-based groups. Federal funding also professionalised the responses to trafficking, namely in the areas of law enforcement and service provision, effectively shutting out survivors and community advocates. Over time, federal funding fluctuations created instabilities to sustain many human trafficking responses.

The year 2006 also saw Colorado enact legislation which defined trafficking in children (§18-6-402 C.R.S., 2006) and coercion of involuntary servitude (§18-13-129 C.R.S., 2006) to accompany legislation for trafficking in adults (§ 18-13-127 C.R.S., 2006), whereby ‘(1)(a) – A person commits trafficking in adults if he or she sells, exchanges, barters or leases an adult and receives any money or other consideration or thing of value for the adult as a result of such transaction; or (b) – Receives an adult as a result of a transaction’. Colorado’s legislation diverged from the TVPA, which created legal challenges for prosecutors. In light of the differences between federal and state legislation, HT 4160 defined human trafficking as ‘a severe form of exploitation for labor (including sex), through the use of force, fraud or coercion’. Doing so allowed for frameworks and lecturers to address a continuum of exploitation, within which human trafficking is situated. It was equally important to link efforts to the work of Colorado human rights trailblazers who paved the way for immigrants, refugees, children, and crime victims, among others; these efforts are named as the work of affinity movements. Establishing a geographic focus and multidisciplinary approach added considerations for shaping content to meet civically engaged learning objectives as the next step in course design.

Drawing upon design structures offered by civic engagement scholars,[15] instructors designing a human trafficking course can incorporate civic activities to support learning objectives through partnerships. This collaborative design allows students to apply theory by learning from community practitioners and engaging with opportunities in the community. For each question posed, examples from HT 4160 illustrate a few decision points.

What are the learning goals of the course? Where can civically engaged learning be infused?

Offer the course from a social justice foundation, countering dominant narratives of human trafficking by focusing on how a global issue affects Colorado communities.

HT 4160’s foundation is grounded in multidisciplinary, intersectional, comparative, and global scholarship of gender studies,[16] where students are encouraged to analyse and challenge structures of inequality inherent in all forms and situations of human trafficking. Social justice frameworks that challenge injustice and value diversity[17] help students understand the history of decision-making power and dominant narratives that frame vulnerability and survivorship.[18] Students first learn to honour the history of affinity movement efforts that were hard-fought and established long before human trafficking was legislated. Students learn to enter communities with humility, developing an openness to learning and personal transformation. For many students, this orientation shifted from a ‘saviour/missionary’ orientation of community service to one attuned to power imbalances and working with community leaders. Students go beyond identifying Colorado’s root causes that create vulnerability to violence and exploitation by also examining the stigma associated with ‘problematic identities’ that create barriers to identification and receiving support and assistance. Pedagogical approaches to support this learning are expanded below.

Building upon its social justice foundation that centralises systemic privilege and oppression, the course incorporated multidisciplinary topics ranging from globalisation, root causes, and economic complexities to legislative and policy development. Discussions and debates have included an array of topics: contrasting federal and state framing of human trafficking; survivor voices and divides; complexities of labour trafficking responses; situating anti-trafficking efforts within labour rights movements; contrasts between chattel slavery and human trafficking; contrasting abolitionist and regulationist approaches to sex work and implications for anti-human trafficking responses; harm reduction efforts for individuals experiencing housing insecurity and managing addictions; human trafficking situated amongst current movements (among them #MeToo; #BlackLivesMatter and #StopAsianHate); COVID-19-exacerbating vulnerabilities for essential workers; and immigration as framed by several federal administrations, among others. Over the years, the course was modified in accordance with changing policies and evolving practices.

In contrast to an international scope with a transnational organised crime focus that was present in 2006, HT 4160 countered global narratives by focusing on Colorado’s community-based efforts to address root causes of human trafficking. The course was designed to illuminate gaps and analyse federal mandates and their impact on Colorado. As new groups emerged to address trafficking, the course content followed suit. Focusing on Colorado allows students to examine how a global issue is manifested at a state level; students can look at differences in geography and how human trafficking is portrayed in the middle of the United States in comparison to locations that have dominated both federal funding and media attention (e.g., large metropolises like New York City, or developing countries in Southeast Asia). Additionally, students learn about trends related to identity-based communities (e.g., vulnerabilities among LGBTQIA communities) and how they inform responses to ending human trafficking in other parts of the world where there may be barriers to inclusion based upon moral and religious values.

With greater focus on evolving community responses, guest speakers[19] provide community-level insight to the successes and challenges in Colorado’s anti-trafficking responses. Students gain knowledge about community resources (e.g., short-term housing), systemic oppression, and gaps that are laid bare by federal and state funding priorities. In the course’s early years, differences between state and federal legislation allowed students to analyse challenges presented by Colorado and federal prosecutors. When the course was first offered in 2007, no cases could successfully use the 2006 state law and statewide public awareness was still in its relative infancy.

As a result of House Bill 14-1273,[20] coupled with infusions of federal funding and persistent efforts to educate the public, anti-trafficking responses have changed and the course has followed suit. HT 4160 has afforded students the opportunity to hear directly from task force and coalition leaders as they coordinate efforts, among them the federally-led Colorado Trafficking and Organized Crime Coalition, and the Colorado anti-trafficking hotline and textline. Students quickly learn that no single sector or discipline can end human trafficking alone.

Structure the course to reflect the field’s multidisciplinary approach and comprehensive multi-sector community response.

The course was first offered in the fall of 2007, situated in Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies (GWS), the home department of the lead faculty scholar. Reflecting the language of the time, GWS 390J, entitled ‘Human Trafficking and Modern Day Slavery’, was initially cross-listed with Africana Studies, Criminal Justice, Honors, Human Services & Counseling, Political Science, Psychology, and Social Work. The cross-listed course design mimics the field, providing students multiple orientations (i.e., human rights, transnational organised crime, and criminal justice approaches) to human trafficking to complement the social justice course foundation. While these departments offer the course as a programme elective, the course meets many programme requirements within all five colleges and schools, inclusive of departments such as Chicana/o Studies, Economics, Hospitality, Education and the Honors programme. Rich discussions co-facilitated by Gender Studies, Chicana/o Studies and Africana Studies faculty have made clear distinctions between the institutionalisation of slavery in the United States and human trafficking as a defined crime. A review of Colorado-focused labour and immigrant rights movements positions human trafficking within the timeline of labour rights action.

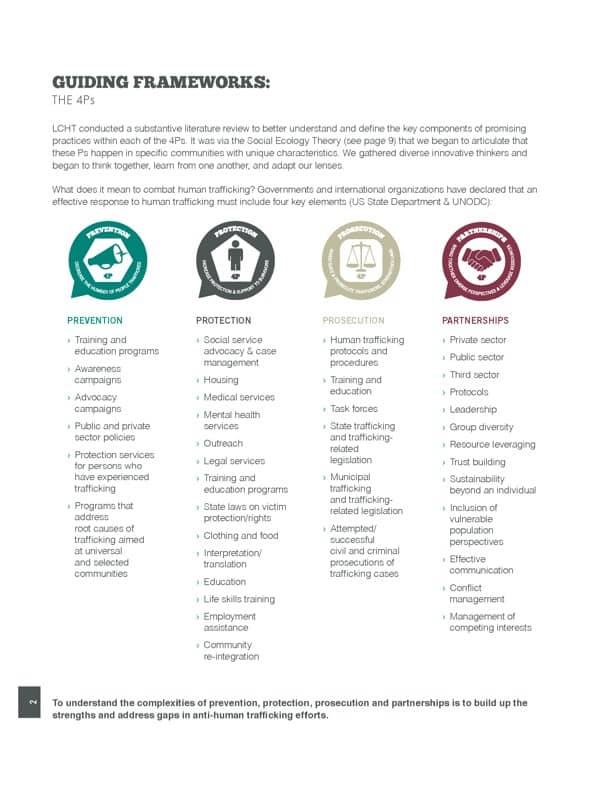

Because of the complexity of multidisciplinary analyses and managing of triggering content, the course was designed as a 4000-level course,[21] abiding by the university’s curricular criteria and the standards put forth by eight departments. Students must go beyond definitions and naming because they are required to analyse, debate, and critique. In 2009, the course was renamed GWS 4160 Human Trafficking, with unanimous support of the cross-listing departments. Initially structured as an in-person sixteen-week course, it has since been offered with every imaginable delivery option: 16-week semester offerings, online, eight-week summer offerings, and two-week intensives. When offered in a 16-week format, HT 4160 dedicates the first eight weeks of content to definitions, theories, and mapping of approaches from a comprehensive response framework, inclusive of the history of Colorado’s affinity movements. The second half of the course is dedicated to application of concepts honouring civic partnerships. This format facilitates deeper discussions and learning practice of theory through guest lecturers and activities. Central to the HT 4160 course structure is Colorado’s research-based, comprehensive ‘Four P’ (4P) framework comprised of protection (services) for trafficked persons, prosecution of traffickers, prevention to keep the crime from occurring, and partnerships among different actors.

What course assignments can be co-created with partnership agencies to support and sustain public awareness and advance social change?

Human Trafficking 4160 developed the role of ‘community practitioners’ to signify guest lecturers representing various perspectives of the comprehensive community response. By design, practitioners, instructors, and students benefit alike, gaining insight into Colorado-based initiatives and challenges. Discussions deepen respect for the complexities of on-the-ground practice, and the third space classroom allows students to inform guest lecturers of their community vulnerabilities and systemic barriers; they regularly pose complex questions from the perspective of their respective majors. Community practitioners benefit from the mix of multidisciplinary questions and course readings, thereby enriching and challenging biases in the way they carry out their work.

As the non-profit partner in the co-creation of HT 4160, the Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking provided important anti-trafficking expertise. In addition to providing longitudinal Colorado-based research to frame the 4P structure of the course, it provided perspectives on the evolution of anti-trafficking responses since its own inception in 2005, when the organisation’s efforts first began as Polaris Project Colorado. As a representative on several task forces and the Colorado Human Trafficking Council, LCHT has engaged its own professional networks to support the course. Of equal importance is that LCHT operates the statewide Colorado hotline and textline, which not only serves survivors and practitioners but also serves as an external resource for students who disclose their trafficking survivorship while they are taking the course.

Community practitioners have included survivor leaders, representatives of the Colorado governor’s council, faith-based organisations providing housing and counselling, prosecutors, sex workers, human rights attorneys, immigration attorneys, interpersonal violence advocates, and outreach workers who conduct their work with individuals located in detention centres, unhoused communities, and farms that employ migrant workers. Law enforcement representatives from State Patrol, FBI, Homeland Security, district attorneys, the Assistant Attorney General for Colorado, and many task force and coalition leaders have also made regular appearances. MSU Denver faculty from Africana Studies, Chicana/o Studies, Criminal Justice & Criminology, Social Work, and Cybersecurity have also contributed to the course. Finally, collaborations amongst Colorado universities enabled students to learn from national and global anti-trafficking leaders on other campuses.

With community practitioners, co-create applied learning opportunities for students.

Since 2007, HT 4160 has incorporated applied assignments designed to cultivate student skill development for social change to support statewide anti-trafficking efforts. Applied learning also channels energies resulting from traumatic material, providing outlets for students to decide if and how they want to engage and take action.[23] During the course, students review the importance of respecting time for how community organisations approach human trafficking (e.g., from a human rights or prosecutorial perspective, among others) and ethical considerations involved in applied field opportunities, among them, the role of reciprocity, respecting community partners, and to do best by the communities served.[24]

Students learn the distinctions between ‘saviour/charity’ and social justice approaches that empower community members to co-create solutions.[25] For example, when services are provided to vulnerable and under-resourced community members who may be historically marginalised, students must attend to unintended consequences of perpetuating this condition for community members.[26] Time is taken to halt notions that by working in the anti-trafficking field, they are there to ‘save’ marginalised communities with their gifts of formal education.[27]

Over the years, students have participated in short-term civically engaged course assignments to support local movement initiatives. These co-designed assignments include: attending Colorado Human Trafficking Council meetings; creating county fact sheets to support Human Trafficking Legislative Day at the capital; delivering two-minute presentations on trafficking to connect content with public interests (e.g., awareness presentations tailored to industries such as hospitality and emergency first responders); writing research papers to support policy briefs and advocacy; offering research support for the statewide Colorado Project and its associated Action Plan; delivering group presentations on the intersections between affinity movements and human trafficking; and crafting critical papers analysing national and global anti-trafficking efforts. During the 2014-15 academic year, students contributed to university-wide public awareness through the annual ‘1 Book/1 Project/2 Transform’ campus event with Runaway Girl by Carissa Phelps. Aligned with the social justice orientation of the course, voluntary opportunities with agencies who do not focus exclusively on anti-trafficking have allowed students a range of opportunities to understand root causes of human trafficking, such as participating in outreach to individuals experiencing homelessness, working with middle schoolers on ‘safe-to-tell’ prevention education, and volunteering on anti-violence public awareness campaigns.

Building a human trafficking course upon a strong foundation of civic engagement principles was a relatively easy task when the opportunity emerged in 2007. However, the delivery of multidisciplinary content from a social justice foundation required an additional set of tools.

What pedagogical tools will aid content delivery to support inclusive learning space?

MSU Denver students are master navigators of personal and systemic community challenges, which requires faculty sensitivities in delivering content on violence and exploitation. For example, many of our students have lived experience with foster care and law enforcement systems that have failed them; others have managed disabilities, combatted trauma, and dealt with food and housing insecurities. Our students come to the course skilled at managing systemic oppression and many do not trust systems and agencies designed to provide social services and uphold the law. Honouring their experience and how they engage with the course content requires sensitivity to trauma.

Trauma-informed course navigation for students begins with instructors communicating clear expectations for participation and content, due to the high probability of secondary trauma and triggering of past trauma. Syllabi provide content, as well as attendance and assessment accountability. Details about expectations for written analyses and critical thinking underscore the nature of an upper division course. On- and off-campus resources (such as the Counseling Center and statewide hotline) are listed to address primary and secondary trauma. Finally, ground rules[28] for respectful discussion and sharing of viewpoints are included to underscore respecting community practitioners and classmates who share their lived experiences. A reading quiz on the second day of class helps students conduct a self-check to see whether they can manage sixteen weeks of content on violence that has the potential for trauma responses. Instructors alike must attend to their own self-care, disciplinary bias (e.g., psychological or criminal justice), trauma response triggers, and boundaries in order to best move students through the content.

During the first days of the course, social justice foundations are laid to sustain trauma-informed facilitation. Taking time to acknowledge individual and cultural levels of trauma must start with a foundation of knowledge defining dynamics of privilege and oppression present in individuals and community systems, such as law enforcement and human services. Further, concepts illustrating the importance of intersectional identity[29] are also reviewed. Seeing others helps with managing secondary and direct trauma to sustain them through the course. Building upon anti-racist pedagogies put forth historically by Freire and hooks, paired with institutional frameworks for Hispanic Serving Institutions, social justice pedagogies shape trauma-informed teaching by acknowledging oppression present in systems designed to support communities (e.g., law enforcement and social services), the ways in which structural violence[30] creates vulnerability and honouring and empathising with others’ lived experiences.[31]

This foundation enables students to understand systems-based inequalities that create barriers to survivor identification, survivor services such as basic needs and counselling, and fair prosecutions. This structure also underscores three levels of inclusion necessary to understanding the complexities of the crime: 1) inclusion of intersectional identities of students, survivors, and practitioners in the classroom; 2) inclusion of multi-sector responses necessary to respond to human trafficking (prevention educators, service providers, and prosecution actors); and 3) inclusion of affinity movement efforts that intersect with the work of human trafficking (e.g., cases that are classified as child abuse that also meet the threshold of human trafficking).

Trauma-informed facilitation tools are critical to the delivery of potentially triggering course content within a collaborative learning community inclusive of instructor(s), students, and community practitioners. Delivery of a multidisciplinary course requires instructors to facilitate complex discussions and attend to secondary trauma triggers that students may exhibit. Instructors and community practitioners with a range of academic backgrounds may not have formal training in trauma-informed teaching, and it is important to forefront this expectation and provide guidelines for all instructors.

Trauma-informed inclusive classroom facilitation involves responsible management of learning entrusted to an instructor’s care.[32] While there is high probability for secondary trauma for most students, there is also likelihood that some student survivors are reframing their lived experiences as they learn course concepts. As stewards of inclusive learning spaces, instructors honour hardship and suffering, while maintaining self-care and boundaries with students. They attend to key principles of a trauma-informed approach, among them safety, transparency, collaboration, empowerment, voice and choice, and honouring cultural, historical, and intersectional identities.[33] Further, they are ready to make adaptations for trauma responses, student disclosures, and referral to resources on campus that go beyond the instructor’s expertise.[34]

Facilitators acknowledge the potential that students may move beyond their comfort zones,[35] and they teach students to respectfully listen to classmates, survivors, and community practitioners who advocate for people experiencing homelessness, race inequity, or the violation of migrant rights or gay and transgender rights, among others. Students learn to analyse societal perceptions of vulnerable communities, where community members who possess ‘problematised’ identities may be missed for being crime victims, or may be perceived as being less worthy of aid. Examples of racially coded identities that hinder identification efforts include terms such as ‘illegal migrants’, ‘truant runaways’, and ‘welfare mothers’. Students learn to reflect on societally-enforced implicit biases associated with these identities and to gather more information in order to determine if they may be potential victims or survivors of crime. Finally, these concepts teach students about the framing of human rights-based initiatives and harm reduction approaches to support vulnerable populations and inclusive social change actions.

Partner with Student Affairs to support student learning.

MSU Denver has many resources for students with a diverse range of identities and experiences. During the first offering of HT 4160 in 2007, Student Affairs units were engaged to provide resources and sustain students while they were enrolled in the course. The course was specifically designed this way to be inclusive and responsive to student needs, and accentuates the ethical and social justice orientation to teaching human trafficking. Inter-institutional partnerships with HT 4160 began with training the vast array of Student Affairs departments to prepare them to support student trauma—whether secondary or triggering—as they learnt course content that featured cases of exploitation and severe violence. Throughout the years, training on human trafficking has been periodically offered to Student Affairs broadly and in individual units, including hotline and textline numbers for tailored resources and referrals. Among these units, the most critical partners have included the MSU Denver Counseling Center, the Health Center at Auraria, and interpersonal violence resources through the Gender Institute for Teaching and Advocacy and the Phoenix Center at Auraria. Other culturally-sensitive student support has been provided through the Center for Multicultural Excellence and Inclusion, ranging from identity-focused resources (e.g., Immigrant Student Services, Veterans Services, LGBTQUIA Services, etc.). Due to MSU Denver’s designation as a Hispanic Serving Institution, most services are offered by bilingual and culturally-sensitive staff. Contact information for all of these resources is noted in the syllabus, along with the offer of accompaniment.

For those who disclose their survivorship, the MSU Denver Student Human Trafficking Academic Response Team (START) provides comprehensive academic case management. Comprised of fourteen MSU Denver Student Affairs units (e.g., registrar or immigrant services) and LCHT, START provides confidential academic case management to advisees who have experienced human trafficking. Since 2007, START has supported sixty-seven survivors of trafficking, most of whom are from Colorado. It is voluntarily staffed by administrators along with students who were formally served by the response team. With guidance from peer case managers, students navigate admissions and registration, and financial aid, among a wide range of student resources. START has been particularly helpful to student survivors as they move through the content they learn in HT 4160.

Incorporate inclusive and reflective pedagogy.

HT 4160’s civic engagement orientation underscores the importance of learning about personal values and one’s identity as a citizen, practitioner or professional. As such, third space classrooms are designed for student well-being by encouraging reflection on the self and world as they learn about human suffering.[36] From day one, the inclusive learning space begins with community-building exercises centred on honouring diverse identities and developing listening skill; trust develops as a community of respectful inquiry emerges. When classroom space allows, positioning desks in a circle helps establish the importance and value of each student’s presence and contribution. Doing so allows all students to be present and situated equally in the front row. Several exercises designed to respect student identities and lived experiences help to check stereotypes and keep students attentive to biases as they contribute to the community of learners. Reflection assignments allow students to deepen their learning by making personal connections with observations and detecting dissonances between theory and practice in the field.[37]

Moreover, facilitating deliberative dialogues has further encouraged students to think about human trafficking. Dialogue allows students to reflect on their own identities and privileges, as well as to recognise their position by learning from others who may have very different identities and experiences. As they listen to community practitioners and classmates, deliberative dialogue can help students better recognise biases in their advocacy positions or beliefs.[38] As part of this facilitation, instructors have been prepared to manage and support student passion and commitment. With an emotionally-laden course, instructors have managed a spectrum of emotions and developmental stages ranging from ‘I care deeply about this issue so I should get an A for my passion’ to social justice warrior entitlement expressed as ‘I am a better advocate because I understand oppression far better than my privilege-blind classmates’. Discussing community vulnerability and oppression has led some students to challenge classmates on their naiveté, and others have laid claim as champions in the ‘compassion Olympics’, where they claim to be the ‘best equipped’ to work in the field. In rarer instances, students have displayed disturbing smiles during harrowing accounts of violence; others have become more determined to become saviour vigilantes or establish undercover rescue operations. The development of humility is part of the journey of civically engaged education, and this careful balance of managing passion and intention can be challenging for instructors to facilitate. Valuing comprehensive community efforts and intersectional identities can curb tendencies to think there is a single correct (or superior) approach to ending human trafficking.

Students on the path to social change work have the opportunity to gain social justice dialogue tools to do the work of coalition-building. The cross-listed structure of this course makes it possible to simulate anti-trafficking community coalitions composed of law enforcement, prevention educators, and social workers, among others. In simulations, students practice inter-sector communication by suspending judgment and identifying assumptions. In post-simulation reflective assignments, they articulate their comprehension of the complexities of responding to human trafficking in a way that builds solidarity and community.[39]

While formal outcomes of Human Trafficking 4160 have yet to be empirically tested, there are proxy indicators of student impact and continuing work in government, business, and non-profit sectors. Anecdotal evidence illustrates how students have taken course knowledge into future endeavours, notably in the ways course alumni enter the workforce with tools and a bias to collaboration for social change.

Civic engagement research has long established the benefits that students gain through this course structure, including stronger civic ties and increased democratic engagement.[40] In HT 4160, many students gained social justice language and tools to address oppression in their own communities.[41] Reflections through discussion and writing assignments have been shown to deepen students’ abilities to make a difference in the world.[42] For courses like HT 4160, civic opportunities have shown positive impact on students beyond persistence to graduation, such as citizenship and political action skills, and how openness to multiple perspectives can truly advance social change.[43]

HT 4160’s final day is dedicated to closure, and we encourage students to continue supporting public awareness efforts with friends, family, and co-workers. Many students realise that they can no longer ignore the possibility of trafficking in their communities. Students leave conscious of their own purchasing behaviours and choices; they understand the importance of tenacious humility and self-care tools in leading social change.

Student evaluations have shared some of the following reflections on HT 4160’s efficacy:

Content delivery was amazing and the environment of the class is amazing; I learned more in this class than [in] any other class in the four years I have been in school.

This course is an eye opener and very necessary for exploring social justice and training for future activists and advocates.

Great reading, deep explanations, and good class discussion—best class I have ever taken. I appreciated the emphasis on self-care and the service-learning opportunities to do outreach.

Pushed me to think beyond the ‘norm’. Great guest speakers give a broad perspective of the issue; the curriculum covered theory as well as many practical examples.

The class is super deep and therefore some of the content is super depressing and carries a lot of emotions; this class has opened my eyes and help[ed] me to have new lenses when observing things in the world.

Other comments gleaned from student evaluations have helped the course evolve and improve with time. For example, feedback regarding the quantity of readings and offering the course during two-week intensives have changed the pacing to allow for greater time for processing and discussion. The challenge of a cross-listed course remains, as different departments have varying expectations of writing, critical thinking skills, and understanding of systems of oppression inherent in many community sectors. During some semesters, the mixed range of readiness of students has led to greater time needed for covering foundational concepts, such as racism and sexism. Course evaluations regularly reflect the diverse range of student preparation. While many students appreciate the rigor and applications, others struggle with reading requirements.

Since some students take HT 4160 intending to enter into the anti-trafficking field, the civically engaged design of the course allows instructors to keep abreast of job opportunities in the field. Today, Colorado agencies focused exclusively upon human trafficking continue to be relatively scarce. Many anti-trafficking sub-programmes continue to be offered in larger agencies serving broader populations with a range of complex needs (e.g., Asian Pacific Development Center, Colorado Legal Services, and Hispanic Affairs Project, among others). Over the years, community practitioners have come to appreciate HT 4160’s comprehensive content, and many regularly forward internship and job opportunities, which are disseminated to students.

With the large percentage of alumni who remain in Colorado, past students have taken the lessons from the course to advance an active and vibrant democracy for the state. Following the course, students have secured non-profit and government internships and positions in the state, including the Colorado anti-trafficking hotline and textline. Others have become Colorado community leaders who think critically as they engage in existing coalitions in their respective fields.

Students have entered careers ranging from law enforcement to service provision, where they take the lenses, sensitivities and co-created knowledge into their future jobs and careers. As important, several former students have been honoured for their survivor leadership, both in Colorado’s communities and nationally. Some alumni share their growth in gaining new language, theories, and frameworks to explain experiences of abuse and exploitation, which enabled them to have closure. Additionally, students’ first forays into anti-trafficking action opened doors to other opportunities, enhanced career paths, and fostered a commitment to social justice work long after they graduate.

Within MSU Denver, anti-trafficking efforts have expanded. The human trafficking course in the Department of Social Work’s Master’s programme focuses on policy development and supports the pipeline from undergraduate to graduate study on this issue. The School of Hospitality launched a Human Trafficking Awareness Certificate as part of its foundational class on Hospitality Leadership, as a way to hold an enriched and competitive edge for alums who enter into Colorado’s industry. Independent studies tailored to the departments cross-listed with Human Trafficking 4160 have also flourished, and several have been presented at the MSU Denver Undergraduate Conference, as well as local and national conferences. Since 2007, the interdisciplinary university-wide Honors programme has featured at least ten theses focusing on human trafficking, launching many students into graduate programmes and professional work in the field.

Civically engaged universities support faculty, students, and community partners primed for social justice and systems change. Beyond knowledge dissemination, there are more nuanced factors that illuminate academia’s role in response to human trafficking both locally and globally. Further work is needed to provide data-informed evidence to measure the impact of academic partnerships on moving the proverbial needle to end human trafficking. As academic institutions evolve ways to respond to human trafficking, bridging research and policy goals and producing civically engaged alumni are a start.

Dr Annjanette Ramiro Alejano-Steele is an Associate Dean in the College of Health & Applied Sciences, and a dually-tenured professor of psychology and gender studies at Metropolitan State University of Denver. She is also the co-founder of the Denver-based non-profit Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking. She is the author of Women and Health: Global lives in focus (ABC-CLIO, 2019). She has served as an advisor on several task forces, and she has researched anti-trafficking responses in Colorado as well as the Global South. She currently serves as an advisor on a global human trafficking research project based in London. Email: alejanos@msudenver.edu

[1] b hooks, Teaching Community: A pedagogy of hope, Routledge, Oxon and New York, 2003, p. xiv.

[2] P Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (revised), Continuum, New York, 2003, p. 61.

[3] Early syllabi designs were gathered by the Protection Project at Johns Hopkins University in a resource database. See https://www.protectionproject.org/donate/association-of-scholars/syllabi.

[4] While the term used throughout this paper references universities, civic engagement efforts also occur in a range of other academic institutions.

[5] J Saltmarsh and M Hartley, ‘A Brief History of the Civic Engagement Movement in American Higher Education’, in C Dolgon, T D Mitchell and T K Eatman (eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Service Learning and Community Engagement, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2017, p. 112.

[6] L J Vogelgesang, ‘Diversity Work and Service-Learning: Understanding Campus Dynamics’, Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, vol. 10, no. 2, 2004, pp. 34–43.

[7] There is a long history of evaluations and meta-analyses on civically engaged partnerships in the community that go well beyond the scope of this paper. See J Saltmarsh and M Hartley (eds.), ‘To Serve a Larger Purpose’: Engagement for democracy and the transformation of higher education, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2011; T H Peterson, ‘Engaged Scholarship: Reflections and research on the pedagogy of social change’, Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 14, issue 5, 2009, pp. 541–552, https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510903186741; D Trudeau and T P Kruse, ‘Creating Significant Learning Experiences Through Civic Engagement: Practical strategies for community-engaged pedagogy’, Journal of Public Scholarship in Higher Education, vol. 4, 2014, pp. 12–30; J A Boland, ‘Orientations to Civic Engagement: Insights into the sustainability of a challenging pedagogy’, Studies in Higher Education, vol. 39, issue 1, 2014, pp. 180–195, https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.648177; S B Gelmon, B A Holland, and A Spring, Assessing Service-learning and Civic Engagement: Principles and techniques, Stylus Publishing, Sterling, 2018.

[8] A Unger, ‘How Higher Ed Survives: Affordable, high-impact civic engagement’, Association of American Colleges & Universities, 19 August 2020, retrieved 15 May 2021, https://www.aacu.org/blog/how-higher-ed-survives-affordable-high-impact-civic-engagement.

[9] E Ward and A Miller, ‘Next-generation Engaged Scholars: Stewards of change’, in P Levine and T K Eatmen (eds.), Publicly Engaged Scholars: Next-generation engagement and the future of higher education, Stylus Publishing, Sterling, 2016, p. 184.

[10] K Gutierrez, B Rymes, and J Larson, ‘Script, Counterscript, and Underlife in the Classroom: James Brown versus Brown v. Board of Education’, Harvard Educational Review, vol. 65, issue 3, 1995, pp. 445–472, https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.65.3.r16146n25h4mh384.

[11] hooks; Freire; R Tarlau, ‘From a Language to a Theory of Resistance: Critical pedagogy, the limits of “framing,” and social change’, Educational Theory, vol. 64, issue 4, 2014, pp. 369–392, https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12067.

[12] MSU Denver’s long history and impact on the communities it has served can be found at https://www.msudenver.edu/our-past/our-history.

[13] G A Garcia, Becoming Hispanic-serving Institutions: Opportunities for colleges and universities, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2019, p. 91.

[14] Throughout the paper, ‘community practitioners’ refers to guest lecturers from various sectors (e.g., government, human services, health, nonprofit) and advocacy groups, including survivor leaders.

[15] S Dudziak and N J Profitt, ‘Group Work and Social Justice: Designing pedagogy for social change’, Social Work With Groups, vol. 35, issue 3, 2012, pp. 235–252, https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2011.624370; Trudeau and Kruse; C Forestiere, ‘Promoting Civic Agency Through Civic-Engagement Activities: A guide for instructors new to civic-engagement pedagogy’, Journal of Political Science Education, vol. 11, issue 4, 2015, pp. 455–471, https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2015.1066684; Peterson.

[16] C M Orr, ‘Women’s Studies as Civic Engagement: Research and recommendations’, A Teagle Foundation White Paper, The Teagle Working Group on Women’s Studies and Civic Engagement and the National Women’s Studies Association, 2011, https://www.teaglefoundation.org/Teagle/media/GlobalMediaLibrary/documents/resources/Womens_Studies_as_Civic_Engagement.pdf.

[17] C Caravelis and M Robinson, Social Justice, Criminal Justice: The role of American law in effecting and preventing social change, Routledge, New York, 2015, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315647432.

[18] For critiques on framing, see A I Fukushima, Migrant Crossings: Witnessing human trafficking in the U.S., Stanford University Press, Stanford, 2019; A Hill, ‘How to Stage a Raid: Police, media and the master narrative of trafficking’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 7, 2016, pp. 39–55, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121773; J Todres, ‘Law, Otherness, and Human Trafficking’, Santa Clara Law Review, vol. 49, issue 3, 2009, pp. 605–672; R Weitzer, ‘The Social Construction of Sex Trafficking: Ideology and institutionalization of a moral crusade’, Politics & Society, vol. 35, issue 3, 2007, pp. 447–475, https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329207304319.

[19] Specifically, survivor practitioners are compensated monetarily for their time, while other practitioners are provided gift cards. In some cases, an exchange of guest speaking for their respective agencies have also occurred to ensure mutual benefit.

[20] ‘Laws and Legislation’, Colorado Human Trafficking Council, n.d., retrieved 10 October 2020, https://sites.google.com/state.co.us/human-trafficking-council/human-trafficking-resources/laws-legislation.

[21] Upper division (4000-level) numbering reflects designation for advanced-level courses in US universities.

[22] ‘Colorado Project to Comprehensively Combat Human Trafficking’, Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking, 2013, retrieved 1 August 2021, https://combathumantrafficking.org/our-research. This 4P framework undergirds the Colorado Governor’s Council and Colorado’s efforts statewide, with the purpose to bring together system-based anti-trafficking efforts from across the state; to build and enhance collaboration among communities, counties, and sectors within the state; to establish and improve comprehensive services for victims of human trafficking; to assist in the successful prosecution of human traffickers; and to help prevent human trafficking in Colorado.

[23] Examples of high-impact applied learning practices include capstone courses, internships and service-learning courses, undergraduate research, and collaborative assignments. See G D Kuh, High-impact Educational Practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter, Association of American Colleges and Universities, Washington, D.C., 2008, https://provost.tufts.edu/celt/files/High-Impact-Ed-Practices1.pdf. For meta-analyses on civic engagement outcomes, see J L Warren, ‘Does Service-learning Increase Student Learning?: A meta-analysis’, Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, vol. 18, issue 2, 2012, pp. 56–61; A Krings et al., ‘The Comparative Impacts of Social Justice Educational Methods on Political Participation, Civic Engagement, and Multicultural Activism’, Equity & Excellence in Education, vol. 48, issue 3, 2015, pp. 403–417, https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2015.1057087.

[24] C Kwan and C A Walsh, ‘Ethical Issues in Conducting Community-Based Participatory Research: A narrative review of the literature’, Qualitative Report, vol. 23, issue 2, 2018, p. 369–386, https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2018.3331.

[25] Boland.

[26] T C Ellington, J A Green and J Kelkres Emery, ‘Civic Engagement I: Experiential and service learning’, in K A Mealy, ‘2013 APSA Teaching and Learning Conference and Track Summaries’, PS: Political Science & Politics, vol. 46, issue 3, 2013, pp. 643–663, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096513000772.

[27] Peterson.

[28] D B Faust and B C Courtenay, ‘Interaction in the Intergenerational Freshman Class: What matters’, Educational Gerontology, vol. 28, issue 5, 2002, pp. 401–422, https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270290081362-2038.

[29] K Crenshaw, ‘Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color’, Stanford Law Review, vol. 43, issue 6, 1991, pp. 1241–1299, https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

[30] K Ho, ‘Structural Violence as a Human Rights Violation’, Essex Human Rights Review, vol. 4, no. 2, September 2007, pp. 1-17.

[31] Boland.

[32] E M Anderson, L V Blitz, and M Saastamoinen, ‘Exploring a School-University Model for Professional Development with Classroom Staff: Teaching trauma-informed approaches’, School Community Journal, vol. 25, issue 2, 2015, pp. 113–134; D Gutierrez and A Gutierrez, ‘Developing a Trauma-informed Lens in the College Classroom and Empowering Students Through Building Positive Relationships’, Contemporary Issues in Education Research (CIER), vol. 12, issue 1, 2019, pp. 11–18, https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v12i1.10258.

[33] ‘SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-informed Approach’, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, July 2014, p. 7.

[34] K M Preble, M A Cook, and B Fults, ‘Sex Trafficking and the Role of Institutions of Higher Education: Recommendations for response and preparedness’, Innovative Higher Education, vol. 44, no. 1, 2019, pp. 5–19, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-018-9443-1.

[35] Dudziak and Profitt.

[36] Examples of these pedagogical approaches are asset-based education, culturally sustaining pedagogy, and active learning. For a toolkit to design learning experiences and empirical support for civic engagement approaches, see Trudeau and Kruse.

[37] L D Fink, Creating Significant Learning Experiences, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2003.

[38] Warren.

[39] These steps include: 1) Forming and building relationships; 2) Exploring differences and commonalities of experience; 3) Exploring and dialoguing about tensions in human trafficking responses; and 4) Action planning and alliance building. See A Alejano-Steele and CA van Minter, ‘Dialogues to Create Justice and Build Coalitions: Key practices on how the Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking is engaging groups across difference and informing a new movement’, National Women’s Studies Association Conference, San Juan, Puerto Rico, November 2014..

[40] Krings et al., p. 410.

[41] J McArthur, ‘Achieving Social Justice Within and Through Higher Education: The challenge for critical pedagogy’, Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 15, issue 5, 2010, pp. 493–504, https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.491906.

[42] D E Giles Jr. and J Eyler, ‘The Theoretical Roots of Service-learning in John Dewey: Toward a theory of service-learning’, Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, vol. 1, issue 1, 1994, pp. 77–85.

[43] J Eyler, D E Giles Jr., and J Braxton, ‘The Impact of Service-learning on College Students’, Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, vol. 4, issue 1, 1997, pp. 5–15.