ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

ISSN: 2286-7511

E-ISSN: 2287-0113

The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

Sam Okyere, Nana K Agyeman, and Emmanuel Saboro

This paper is a critical reflection on the ethical and political issues associated with the creation and dissemination of unsettling images and videos for child trafficking and human trafficking abolitionist campaigns. The paper acknowledges efforts by anti-trafficking campaigners to address accusations of poverty porn, stigmatisation, and sensationalism directed at such visual propaganda. However, it also observes that these remedial measures have had very little impact. Anti-child trafficking and anti-human trafficking campaigns are still dominated by sensational spectacles of victimhood, abjection, pain, and suffering. The paper attributes this inertia to campaigners’ fears that radical deviation from the use of emotive or ‘biting’ visuals may undermine their established narratives, campaign goals, and even credibility. It supports this conclusion using path dependence theory and the findings of research with residents of remote island communities on the Lake Volta in Ghana who have been the focus of extensive anti-child-trafficking raids and campaigns over the last decade.

Keywords: Volta, Ghana, child trafficking, abolitionist

Please cite this article as: S Okyere, N K Agyeman, and E Saboro, ‘“Why Was He Videoing Us?”: The ethics and politics of audio-visual propaganda in child trafficking and human trafficking campaigns’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 16, 2021, pp. 47-68, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201221164

As we got close to the shore, two speed boats dashed at us through the fog, almost capsizing our canoe. The occupants were armed, and they said they were the police. They pointed their guns at us and said I am under arrest for working with children on the lake. They told my children to get into their boats. We were all petrified. The children were screaming and clinging tightly on to me to avoid being taken. I tried to explain to them [the police] that these were my own children and we had gone to catch fish to feed our family, but one of them hit me for not complying with their order. They snatched my children into one boat, pushed me into the other and took us away. They put me in the police cells for three days, after which they let me go without charge. But it has been almost a year now and I do not know what has happened to my stolen children. (Kwame, Akakpo Island).

Since 2015, some anti-trafficking NGOs have partnered with the Anti-Human Trafficking Unit (AHTU) of the Ghana Police Service and other government agencies to conduct anti-child trafficking raids across the remote island communities on the Lake Volta in Ghana. The quote above is an extract from our interview with Kwame, a father who was recounting how three of his children were, in his words, ‘stolen’ by the AHTU and an NGO which raided his community, Akakpo, and three other islands, Anakpokpo, Kpala, and Gasoekope, in 2017. The AHTU and the NGO removed a total of 144 children from the four islands under the suspicion that they were victims of trafficking or ‘modern slavery’. However, according to the Member of Parliament for the islands, after investigations that went on for nearly a year a different reality emerged. In contrast to the belief that the children had been rescued from ‘traffickers’ or ‘slave masters’, it transpired that all but four had been wrongly snatched from their families. As Kwame lamented, his children and many others had been traumatised by the violence of the supposed rescue and by being held by the authorities for nearly a year during which they were denied contact with their families.

This egregious outcome notwithstanding, the NGO and AHTU have persisted with the raids. Images and video footage captured during the raids and those of allegedly rescued children form a central plank of the NGO’s anti-child trafficking advocacy and fundraising initiatives. The creation and use of such controversial audio-visual materials for campaigns, fundraising, and other advocacy is a widespread and long-standing practice in the anti-trafficking and humanitarian fields. Selling human misery and suffering is one of the primary currency earners for humanitarian organisations, as Kennedy puts it.[1] In the child trafficking context, it is justified as a means of speaking for victims who supposedly lack the voice, agency, and capacity to speak for themselves.[2]

However, this visual propaganda also raises intractable moral, political, and ethical concerns. It has been denounced as degrading, distortions of reality, needlessly melodramatic, commodification of suffering and epistemically violent.[3] Anti-trafficking and humanitarian campaigners have duly acknowledged these concerns and articulated various remedies in response. These include the adoption of ethical codes to guide campaigns,[4] commitments to the use of less problematic images,[5] and the elicitation of ‘survivor voice’ to guide campaigns.[6] Yet, child trafficking and human trafficking prevention and abolitionist campaigns are still largely dominated by spectacles of abjection, victimhood, pain, and suffering. Indeed, even in instances where more measured images and videos are used, the themes of pain and suffering are retained through selective representations that provide narrow understandings of complex issues and may thus misinform. What accounts for this inertia?

This paper examines this question drawing on findings of research conducted with residents of the raided islands and anti-trafficking NGO staff. Using the participants’ accounts and a path dependence theoretical framework,[7] the paper argues that the lack of change results from the fact that some anti-trafficking organisations are hemmed-in by their established campaign messages and strategies. The inertia arises in part from the concern that audiences who have been (de)sensitised through prolonged exposure to melodramatic visuals of victimisation, pain, and suffering may not respond in the same way to less ‘biting’ or ‘gripping’ images and narratives. Sensationalism and shock thus prevail because they are seen as easier routes to successful awareness-raising, fundraising, and other goals compared to careful analyses of the complexities surrounding children’s work and mobility. The paper concludes that this logic and the raids to which it contributes have to be tackled to promote a more comprehensive understanding of the rights issues facing the remote islands and other marginalised communities that are the focus of anti-trafficking campaigns.

The creation and dissemination of unsettling images and videos have become ubiquitous in child trafficking advocacy since adoption of the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (ILO C182) and the UN Trafficking Protocol in 1999 and 2000, respectively. This trend firstly reflects campaigners’ desire to harness the power of audio-visual propaganda to simplify or sidestep debates on the thorny political, economic, and socio-cultural issues surrounding trafficking.[8] Secondly, such controversial campaigns are seen as a means of showing the realities of child trafficking and human trafficking to audiences.[9] They are deemed to ‘confer reality status’ or lend credibility and urgency to situations that might otherwise be deemed unbelievable.[10] The third reason is funding. Faced with growing competition for attention and funding, sensational representations of allegedly trafficked, exploited, and abused children are deployed in an attempt to shock audiences into attention and hopefully loosen their purse strings in turn.[11]

In the child trafficking context, this mode of campaigning serves important ideological functions related to normative ideas about children and childhood.[12] Images and videos of allegedly victimised, abjected, and disempowered children conveniently reinforce notions of children’s innocence, naivety, and supposed lack of capacity to speak up for themselves.[13] As the NGO Humanium states in an anti-child trafficking campaign featuring images of children in chains and tears, this presentation gives ‘voice to voiceless children...young lives unaware of their own rights and unknowingly sold for their bodies like oil or a Persian commodity off the side of a crowded Sunday bazaar’.[14] Additionally, in media and popular culture, children’s images and videos are typically used to elicit or denote joy, innocence, and happiness.[15] The use of disturbing images of allegedly trafficked, abused, and suffering children is intended to upend these romantic visions and convey messages about lost and broken childhoods in need of rescue.[16]

These controversial representations have been roundly criticised. Across the wider humanitarian field, campaigns featuring images of children or others in deplorable and abjected states are castigated as typecast representations and stereotypes which produce stigma and discrimination.[17] Those featuring black and brown children from the Global South who have supposedly been trafficked and abused by their own relatives and communities and instead rescued by a (often white Global North) benefactor have also been criticised for reinforcing harmful tropes about the supposed ‘sorry’ and ‘uncivilised’ state of non-white communities in need of white ‘benevolence’, ‘civilisation’, or ‘salvation’.[18] Holly also argues that images and films can ‘talk’ to their consumers in ways that can be radically different to those intended by their makers.[19] Hence, jarring scenes intended to simplify or sidestep the complex social, economic, and political questions around childhood, children’s work, and mobility can instead confuse and convey simplistic, erroneous and even harmful understandings and responses.

Some of these concerns have emerged from within the anti-trafficking sector itself, leading to a range of remedial measures over the past decade. Numerous anti-trafficking campaigners, scholars, activists, and other stakeholders have advocated for the adoption of ethical codes of conduct to guide campaigns, a shift towards the use of less unsettling images and videos, and the inclusion of ‘survivor voice’ in campaign development and dissemination.[20] Organisations such as Save the Children, for example, increasingly avoid using actual images of children for their child trafficking campaigns, opting instead for cartoon abstracts, illustrations, and silhouettes. However, the impact of these remedial measures has thus far been underwhelming because anti-trafficking campaigns still largely seek to attract attention, funding, and other support through motifs and themes of pain and suffering. Hence, despite using children’s silhouettes in place of real images, Save the Children’s videos state ‘...you won’t see their faces, but you will hear their stories and feel their pain’.[21]

The ethical questions and slow remedial rate are probably most acute in campaigns featuring images and videos taken during trafficking raids. These representations provoke serious questions about consent, anonymity, and dignity given the often clandestine, oppressive, and violent conditions under which they were produced. The legitimacy of capturing videos and pictures in anti-trafficking raids is defended by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Ghana as a means of securing evidence for prosecuting alleged perpetrators.[22] Yet, the many documentary films and campaigns featuring such media show that their primary function is emotional sensationalism rather than legal redress. In some instances, instead of alleged perpetrators, video and pictures of allegedly rescued children are used with the justification that ‘survivor voice’ or representation is also crucial for anti-trafficking advocacy.[23] Some take the utilitarian view that there is no problem if ‘survivors’ willingly consent to be presented as objects of pity for awareness-raising, fundraising, and other anti-trafficking advocacy.[24] Yet, what may be instrumentally convenient may not necessarily be ethical.

The issue is not simply whether ‘survivors’ agree to be presented as objects of degradation and misery, but whether their consent is genuine and voluntary when their access to food, shelter, and other support is often contingent on accepting the ‘victim’ or ‘survivor’ label or cooperating with the narratives and expectations of their ‘rescuers’. ‘Survivor’ voice can merely serve as a fig leaf for rubber-stamping the preferred modalities of ‘rescuers’ in such cases where inducements are involved.[25] Furthermore, genuine voluntary informed consent is arguably not possible when people are unaware that the ways in which they are portrayed feeds into practices and discourses that cause harm, or the benefits they envisage from accepting to be presented in this way may not, in fact, materialise. This is clearly borne out by evidence that children who were presented as having been rescued from trafficking or slavery in fishing communities on the Lake Volta have ‘re-trafficked themselves’ back to their supposed former ‘slave masters’ upon realising that the promises of education, food, money, and other benefits by their ‘rescuers’ will not materialise.[26]

In the next section of the paper, which presents the Lake Volta research, we argue that the meaningful resolution of these complex issues of representation, rights, (un)freedom and social justice requires a shift from the low-hanging fruits of sensationalism and melodrama in favour of accounts that deal with the complex social, economic, political, and cultural factors surrounding children’s work and labour mobility.

This paper is based on field research conducted in July 2018 in Gasoekope, Akakpo, Anakpokpo and Kpala, four remote island communities located on the Volta Lake in Ghana. The lake, which is the largest human-made reservoir in the world, was formed between 1961 and 1965, when around 3,000 square miles of land were flooded for construction of the Akosombo hydro-electric dam. Per the accounts of elders during the fieldwork, during this period, residents of some affected communities who were engaged in fishing moved to coastal Ghana and other locations where they could continue this work. Following the dam’s construction, some resettled on the dozens of islands that had formed on the lake. These returnees were joined by coastal fishermen and others looking to take advantage of the bountiful catfish, perch, tilapia, and other species that were now thriving in the lake’s warm waters. All aspects of life in these island and riverine communities revolve around the lake. It is the residents’ main livelihood source, marketplace, social and recreational ground, and highway to other islands.

Over the years, depleting fish stocks, deforestation, and climate change have resulted in marked deprivation across the islands. The islanders’ socio-economic hardship is also linked to their exclusion from government social welfare, infrastructure, and development programmes owing to their geographical remoteness. All four islands involved in this study have no electricity, roads, hospitals, potable water, or other basic infrastructure and services. Against this backdrop, families deem it crucial to teach their children fishing skills to support household subsistence and guarantee their children’s self-sufficiency in adulthood. Much respect and honour is also associated with the ability to subsist independently through work on the lake and the land. Adults who lack such abilities are sometimes ridiculed even where they have other income sources. Families typically introduce their children to fishing once they are able to swim, with their tasks based on their maturity, gender, and experience. Boys are usually expected to watch over the canoe during fishing and help with mending, casting, and retrieving nets under adults’ supervision. Girls are typically involved in processing and selling the catch.

As Okyere has detailed elsewhere, the last decade has witnessed intensive efforts by numerous domestic and foreign anti-trafficking organisations, media and other actors seeking to present and address such forms of children’s work on the lake as outright forms of child exploitation, child trafficking, and child slavery.[27] They claim that thousands of children have been bought for nothing at all or for as little as USD 20 in Ghanaian coastal areas such as Winneba and trafficked to the islands where they are forced to labour for nearly 15 hours daily, with no chance of escape.[28] These harrowing accounts and portrayals of ‘child slavery’ and ‘trafficking’ on Ghana’s Volta Lake have attracted significant international attention, including documentary films and reports by the BBC,[29] the Guardian,[30] and CNN.[31]

We do not dispute the possibility that children’s work in these communities can be exploitative and abusive. The many documented cases of egregious child exploitation in schools,[32] care homes,[33] the church,[34] and even within NGOs purportedly seeking to rescue abused children[35] teach us that child victimisation can occur even under seemingly benevolent or benign conditions. However, we maintain that there are serious questions about the narratives and scale of the problems reported given that there has been no independent large-scale survey or studies to test the veracity of these claims. Much of what is known about the issue is drawn from small scale studies conducted by the NGOs for their advocacy. There are more serious questions still about the appropriateness of the ‘child catching’ raids that have become one of the main responses to the issue.

The main objective of our study was to explore these raids of which there has been no research, legal, or other scrutiny to date. Thus, a key point of originality and value-addition by this paper to debates on trafficking, human and child rights and humanitarianism is that it is the first scholarly critique of this ongoing practice in the specified social and geographical context. In contrast to anti-trafficking NGOs, the AHTU and others’ depiction of such interventions as ‘rescue missions’, the paper employs the terms ‘raids’, ‘child stealing’, and ‘theft’ in keeping with the participants’ descriptions of the NGO’s and AHTU’s operations in their communities. Use of the terms is also in line with the study’s aim of amplifying the islanders’ views and experiences, which have long been excluded from debates on children’s work, mobility, and socialisation in their communities. The results of a basic Google search with the terms ‘children’s work lake Volta’ shows that dominant representations of children’s work on the islands are characterised by stories of good versus evil. NGOs, media, and other mainline actors present the islanders as malicious child traffickers, enslavers, and exploiters on one hand and cast themselves as benevolent agents seeking to save trafficked and enslaved children let down by their own parents, families, and communities, on the other.[36]

The study was therefore firstly interested in the islanders’ views on this representation. Secondly, we wanted to explore and amplify the islanders’ experiences of, and views on, the raids and the overarching accusations of pervasive child trafficking and enslavement levelled at their communities. We employed a qualitative sequential multi-method research design with the rationale that using more than one method would offer different but complementary data that could provide a more profound understanding of the issues.[37] In practical terms, we started with a community-wide meeting on Gasoekope island and focus group discussions on Akakpo, Anakpokpo, and Kpala islands to explore the residents’ opinions on the research topic. Following these group meetings, we conducted eighteen in-depth qualitative interviews with families of children who were taken during the raids, traditional leaders, and elected political representatives. We also conducted five interviews with staff of anti-trafficking organisations, primarily to explore with them the islanders’ views on their operations.

The interview and group meetings’ data were analysed thematically following the process outlined by Braun and Clarke.[38] A more detailed account of the raids and their aftermath is discussed in a forthcoming paper by the authors. Due to word count limitations and to maintain the paper’s central focus, we present two thematic findings related to the capture and use of visual materials for anti-trafficking advocacy: the white man with the camera and the politics of representation.

An issue about which the islanders expressed immense disquiet was the presence of ‘the white man with the camera’. They were referring to a white staff member of the NGO who was with the raiding party. The NGO in question concedes in its published documents that staff members accompany local police on ‘rescue missions’ though they only play a supporting role. However, the islanders were adamant that the ‘white man with the camera’ was more than an observer or supporter. They insisted that he was largely in charge of the operations, directing the police to take their children, brothers, grandchildren, and relatives while calmly recording the ensuing violence and dehumanisation.

We all saw him. He [the white man] was in the other speed boat with a camera telling them what to do and recording them [the police] taking my son from me. I shouted at him to stop pointing it [camera] at me, but the police hit me. (John, father, Gasoekope)

As we were nearing the shore, I saw the white man with the camera. He was pointing something at us. Later, they [other islanders] told us it was a camera. He pointed it at us all the time, even when my brother was crying as the men with guns took him away. (Kwame, brother, Kpala)

They [police] came with the white man with the camera to steal our children. He was in another boat watching everything with his camera. Why was he doing this? (Kobla, grandfather, Akakpo)

Throughout the interviews and group meetings, the islanders repeatedly pondered why the white man was recording them. The persistence of this point drew our attention to the fact that they were completely unaware of the use of such videos for anti-trafficking propaganda. The islands’ lack of electricity, televisions, computers, and access to the internet, coupled with their remoteness, meant that none had seen any of these videos before. We therefore showed them some of these videos on the internet using our laptops. Their reactions ranged from incredulity to distress and anger. As Ablah, a grandmother on Kpala island lamented, the videos added insult to the injury of their brutalisation and the theft of their children:

First, they come to beat us, steal our children and leave us in fear. Now we find out they have also been using the videos to disgrace us.

Abu, the leader of Akakpo island, also complained that the videos wildly exaggerated the nature of children’s involvement in fishing in their communities, while completely omitting the violence visited on his community by the raiding parties.

Watching this film, I can see that they [anti-trafficking campaigns] don’t talk about how they came to beat my people. Some run into the bushes in fear and didn’t come back for days. Nobody in the videos talks about this, except their lies that we buy children and force them to work for us. I can swear before any deity that we do not live the way they [NGOs] are saying in these videos. I have six children and I also raised three of my sister’s children who were sent to live with me here. I taught them all how to work on the lake and they are also teaching their children because that’s how we all take care of ourselves here. They [NGO and police] refuse to understand us. They took three of my grandchildren away and I am in deep pain.

In sum, the islanders were firstly angered at being recorded without their consent during the raids. They then also contested the credibility of the anti-child trafficking campaigns and documentary films for which the recordings had been used. They were adamant that these were distortions of children’s socialisation and work in their communities. As we discuss next under the second theme, the politics of representation, they felt that it was possible to raise concerns about their children’s lives and work without raiding their islands or using materials which indiscriminately stigmatised them.

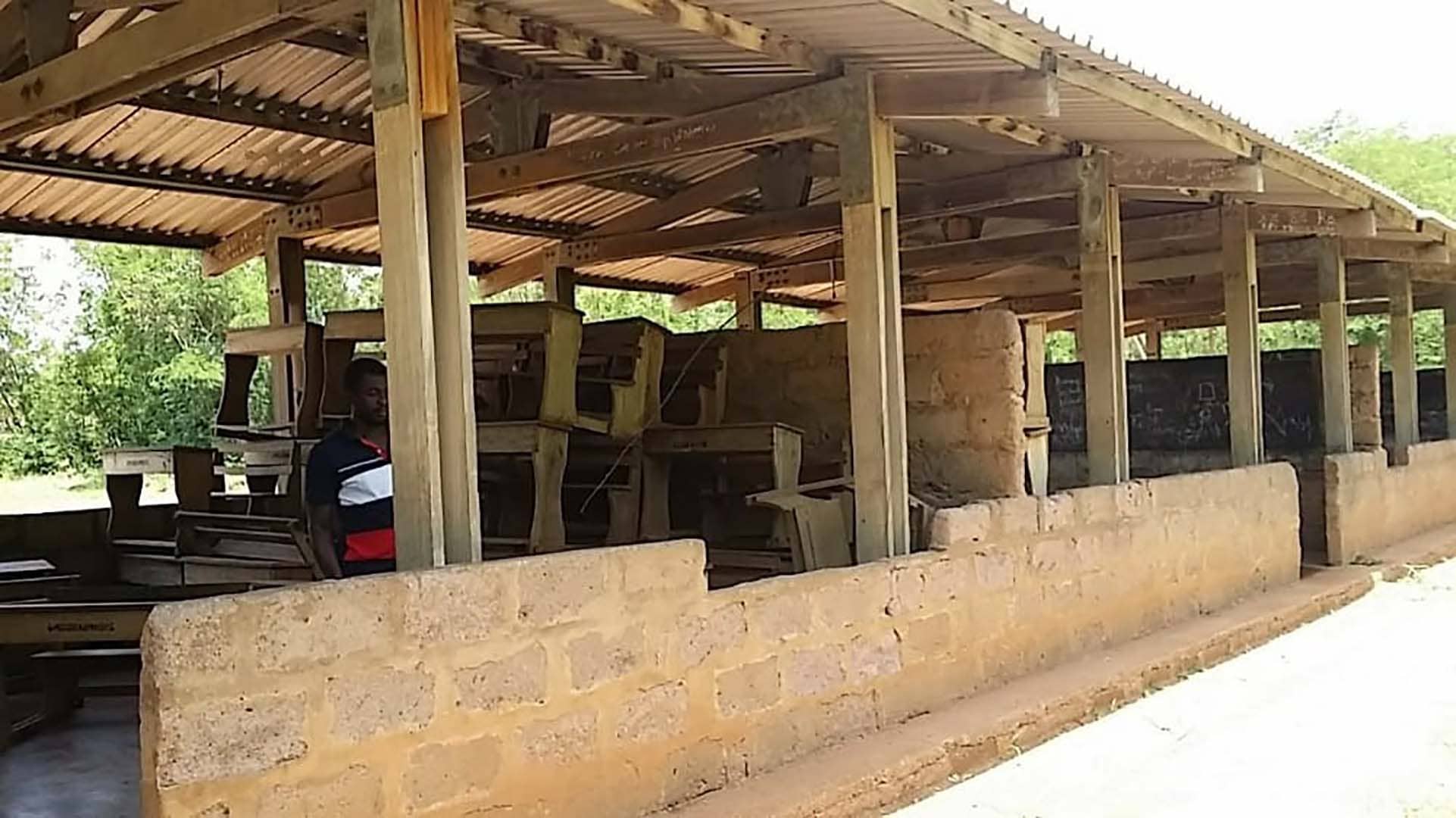

Much as the islanders defended the permissibility, desirability, and appropriateness of children’s work on the lake, they also acknowledged that it can be challenging and even perilous for very young children and those who cannot swim. Many noted that they would like their children to attend school and attain other skills in addition to fishing, such that they could seek opportunities outside the islands if need be. However, as Alex, a parent, exclaimed, schools and other opportunities were non-existent on their marginalised islands: ‘They arrested me for being on the lake with my sons instead of taking them to school, but where is the school?’ Akakpo and Anakpokpo islands have never had schools while Gasoekope’s was destroyed by rainfall at the time of the fieldwork. Kpala island had a school building with six classrooms, three of which were structurally unsafe at the time of the fieldwork. A fatal accident was narrowly avoided barely a month earlier, when one of the walls collapsed while pupils were playing outside during their lunch time. Consequently, all pupils from classes 1–6 concurrently use the remaining three classrooms. To further compound matters, the entire school had only two untrained volunteer teachers. Qualified teachers posted to Kpala and the other remote islands refuse to travel to these duty stations because of the islands’ remoteness and the lack of infrastructure and opportunities for career and social mobility.

The islanders questioned why these pressing educational and developmental needs, which in part inform their children’s work on the lake, do not feature in the anti-trafficking campaigns and documentary films. We saw this as a reflection of media and anti-trafficking campaigners’ continued preference for sensationalism and simplistic stories of good versus evil over engagement with the complex social, economic, and political issues that often lie behind children’s insecurities. For the islanders, however, there was more to this omission. As this quote from our interview with Mary, a mother on Akakpo island, shows, they saw it as a deliberate measure to justify raiding their islands to capture their children: ‘Why don’t they [NGO and police] come and help us build our schools or support us to cater for our children if they say they care about them? Can they care more about our children than us? They say these things [claims of child trafficking and slavery on the islands] so that they can come to take our children from us.’

Given the strength of their belief in this assertion and feelings that the campaigns were distortions of children’s work in the communities, we asked Mary and others to propose alternative images to be used for a campaign on the subject. They asked us to take photos of their crumbling school block to explain why their children go to fish instead of attending school. They also asked us to take photos of their torn fishing nets, broken baskets, and dilapidated homes to convey to the outside world that their children were not victims of trafficking and slavery, but victims of socio-economic deprivation and lack of opportunities. As Ama, a mother on Anakpokpo island, told us: ‘If we had enough money, we would even send our children away to stay with my sister at Hohoe for education instead of fishing with us here. But our canoe is always leaking, we need new nets, and we can’t catch enough fish. We are on our own here, no help from anywhere.’

In response to such arguments, some argue that poverty and structural hardships do not justify children’s harmful labour.[39] The question of whether children’s fishing activities with their families on the islands are harmful and exploitative is not the main focus of this paper; neither is it seeking to trivialise or idealise children’s precarious labour. However, even if claims that children’s work on the island is unequivocally harmful are valid, we found the islanders’ accounts equally persuasive if not more so. They showed that, while structural conditions such as poverty and marginalisation are key determinants for their children’s work on the lake (harmful or otherwise), these causal factors are trivialised or not addressed by anti-trafficking advocates. When we raised this issue in our interviews with the NGO staff, they were similarly sympathetic to it. Yet, even as they acknowledged the problematic nature of the raids and portrayal of the islanders, they expressed scepticism as to whether a step change in their sector was going to occur any time soon. As one candidly explained, raids and their related campaigns are also driven by funding considerations, which may not be met by focusing on socio-economic factors as demanded by the islanders:

We are concerned about children’s rights, but the issue needs funding. Donors want to see results, and sometimes it takes raiding the communities to attain the numbers and get the images needed to touch the hearts of donors. It is all about funding in the end. How much they [an organisation] raise is dependent on how many ‘rescues’ they do. It is sad but that is the reality.

Furthermore, such change may not occur because there is no dialogue between some NGOs and the communities that are the focus of their campaigns, as another added:

Tell me, how would they [NGO involved in the raids] understand and appreciate the community standpoint of childhood and child labour when they refuse to acknowledge their existence? How would they appreciate the needs of the community when they do not go to talk to them? We go and seek to deal with the communities and the underlying socio-economic challenges that they face. If you look carefully, you can tell that our strategies and focus are different from theirs.

We draw on the theory of path dependence to examine this situation in the discussion and conclusion section that follows.

This paper is a contribution to critical scholarship on the ethical and political issues associated with the creation and dissemination of unsettling images and videos for child-trafficking and human trafficking abolitionist campaigns. Its key argument is that the anti-trafficking sector’s efforts to remedy the problems associated with such campaigns have been largely rhetorical or superficial. Sensationalism and spectacles of victimhood, abjection, pain, and suffering still dominate anti-trafficking campaigns, documentary films, and other depictions. The paper’s explanation for the persistence of these unethical strategies is that some anti-trafficking actors are trapped by their rhetoric and history, per the theory of path dependence. This theory is used by sociologists, economists, and political scientists to explain how existing practices, systems, and ideas can create inertia after so much has been invested in them.[40]

Its departure point is that history and precedence (choices, ideas, practices, and behaviours) matter immensely and can create heavy disincentives for change.[41] The functioning of societies and institutions is such that initial choices and events set into motion specific trajectories which can become difficult to change in time for reasons such as cost, time, rules, credibility, and other factors. Consequently, they are maintained and even defended when they are shown to be flawed.[42] In this case, the NGO and other actors have carved for themselves the unique and unquestionable authority to determine what counts as valid knowledge on children’s mobility, work, and socialisation on the islands. They have established a three-component narrative of helpless child trafficking victims, evil traffickers or perpetrators in their own communities, and heroic outsiders such as anti-trafficking NGOs.

Their stories of child abuse, trafficking, and enslavement in this area have attained international recognition as unassailable ‘truths’ and dominate the mental frames through which children’s work on the lake is presented and understood. Path dependence analysis suggests that such power and privilege can equally constrain. Deviation from these messages, which have so far been presented as sacrosanct, can appear as an acknowledgement of fault. Acceptance of positions such as those from the islanders that have been omitted, concealed, or invalidated for so long can also appear as a threat to credibility, authenticity, and consistency. Consequently, the white man with the camera, the AHTU, and other anti-trafficking campaigners have become resistant to change. The inertia is also connected to the hugely unequal power differentials between the marginalised islanders and the raiders which include politically influential and well-connected organisations worth over USD 60,000,000, the AHTU which is a state security apparatus, and global media organisations such as the BBC and CNN.

Change has become difficult for the NGO and other anti-trafficking actors because the raids also serve as the means through which they are able to create videos, images, and other resources through which they claim expertise and power of social construction over the realities of children’s work on the islands. Moving away from this mode of operation towards community engagement risks humanising the islanders who have long been caricatured as irredeemable villains in the anti-trafficking campaigns. Such change could shatter the tales of good NGO saviours versus evil islanders and potentially dry funding streams as our NGO interviewees intimated. Hence, despite the widespread awareness within the anti-trafficking sector that raids and controversial campaigns flagrantly violate the rights of entire communities, a move away from these practices does not seem likely; especially so because there is currently no realistic prospect for sanctions against the rights violations associated with the raids given the aforementioned political, social, and economic power imbalances between the islanders and raiders.

Further, continuation of the status quo also rests with audiences or those who engage with the campaigns and documentary films. Research shows that prolonged exposure to sensational, melodramatic, or unsettling visual materials can numb audiences to less dramatic representations.[43] Comparatively ‘anodyne’ images such as those proposed by the islanders may therefore not find sufficiently fertile sympathetic grounds. To agree with Kennedy, the continued domination of ‘hard-hitting’ images in humanitarian campaigns signifies the paradox that audiences have also come to expect representations that strip supposed child victims and their communities of all social, political, and cultural significance and present them in a state of ‘bare life’, as Agamben puts it.[44] The impetus or moral inclination to support others no longer hinges on solidarity and dignity but the degree to which they are or can be presented and accepted as ‘suitable victims’ or worthy objects of pity, victimisation, and degradation.

The foregoing is all the more problematic when we consider that anti-trafficking interventions of this kind and charity appeals in general are rarely ‘solutions’. The islanders’ accounts show that these are mostly reactions to manifestations of more profound social, economic, and other structural problems. A shift from sensationalism, melodrama, and raids towards community collaborations and more informed conversations on the social, educational, economic, and other underlying drivers of children’s insecurities is therefore urgently needed. This includes the need for further research to better understand how adults and children alike in communities such as those on the Lake Volta understand harm, exploitation, child development, family relationships, freedom, and unfreedom.

To conclude, we do not argue that the use of images and videos is in and of itself problematic. Used sensitively and with the full consent and involvement of those who are featured, they can be a good means of advocating for the rights of disenfranchised persons and communities. However, we reject the use of visuals acquired through anti-trafficking raids given the serious ethical questions and outright human rights violations surrounding the acquisition and use of such materials.

We are immensely grateful to members of the European Research Council (ERC)-funded project, Modern Marronage: The Pursuit and Practice of Freedom in the Contemporary World (ERC ADG 788563); Julia O’Connell Davidson, Angelo Martins Jnr, Pankhuri Agarwal, and Jose Nafefe for their generosity, expertise, and extremely helpful comments on early drafts of this paper. The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this essay. However, ongoing work on the aforementioned ERC project has been instrumental in shaping our thoughts for the essay, and for that we are grateful.

Sam Okyere is a socio-anthropologist and Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies (SPAIS), University of Bristol. He is primarily interested in the linkages between human and child rights, power, class, ethnicity, (un)freedom, inequality, globalisation, and the legacies of slave trade and colonisation, mainly but not exclusively in African contexts. Over the past decade, he has explored these issues through extensive field research on child and youth labour (in agriculture, mining, fishing, and other sectors) migration, artisanal mining, sex work, forced labour, trafficking, and other phenomena popularly labelled as ‘modern slavery’. Email: sam.okyere@bristol.ac.uk

Nana K Agyeman is an expert in international human rights law, public international law, and public law. He is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Law, Policing and Forensics, Staffordshire University. He is interested in the intersections (if any) of international law and international policing on the question of criminal jurisdiction in Africa. His recent research is on ‘policing’ rescue operations of anti-trafficking NGOs in Ghana to present a counter-narrative. Email: nana.agyeman@staffs.ac.uk

Emmanuel Saboro is a Senior Lecturer at the Centre for African and International Studies, University of Cape Coast, Ghana, and a fellow of the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS), African Humanities Program. He is an interdisciplinary scholar with research interests centred on the use of literature, folklore, and oral history for explorations of the impact of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade on Africa, literary manifestations of the slave experience, nineteenth- and twentieth-century African abolitionism, and anti-slavery discourses. Most recently, his research has focused on memory, trauma, resistance, and identity construction in northern Ghana. Email: esaboro@ucc.edu.gh

[1] D Kennedy, ‘Selling the Distant Other: Humanitarianism and imagery-ethical dilemmas of humanitarian action’, The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, vol. 28, 2009, pp. 1–25, https://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/411.

[2] ‘Trade of Innocents: Film captures reality of child trafficking for sexual exploitation’, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 28 September 2012, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2012/September/trade-of-innocents_-film-captures-reality-of-child-trafficking-for-sexual-exploitation.html; H R Evans, ‘From the Voices of Domestic Sex Trafficking Survivors: Experiences of complex trauma & posttraumatic growth’, Doctorate in Social Work Dissertations, University of Pennsylvania, 2019, https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2/126.

[3] L P Beutin, ‘Black Suffering for/from Anti-Trafficking Advocacy’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 9, 2017, pp. 14–30, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121792; M Lim and M Moufahim, ‘The Spectacularization of Suffering: An analysis of the use of celebrities in “Comic Relief” UK’s charity fundraising campaigns’, Journal of Marketing Management, vol. 31, no. 5–6, 2015, pp. 525–545, https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1020330; J Repo and R Yrjölä, ‘The Gender Politics of Celebrity Humanitarianism in Africa’, International Feminist Journal of Politics, vol. 13, no. 1, 2011, pp. 44–62, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2011.534661; T R Müller, ‘The Long Shadow of Band Aid Humanitarianism: Revisiting the dynamics between famine and celebrity’, Third World Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 3, 2013, pp. 470–484, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.785342.

[4] United Nations Inter-Agency Project on Human Trafficking, Guide to Ethics and Human Rights in Counter-Trafficking: Ethical standards for counter-trafficking research and programming, Bangkok, September 2008, http://un-act.org/publication/view/guide-ethics-human-rights-counter-trafficking; L Rende Taylor and M Latonero, Updated Guide to Ethics & Human Rights in Anti-Human Trafficking: Ethical standards and approaches for working with migrant workers and trafficked persons in the digital age, Issara Institute, Bangkok, 2018, https://respect.international/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Updated-Guide-to-Ethics-and-Human-Rights-in-Anti-Trafficking-Ethical-Standards-for-Working-with-Migrant-Workers-and-Trafficked-Persons-in-the-Digital-Age.pdf.

[5] E Brady, Photographing Modern Slavery: Recommendations for responsible practice, University of Nottingham Rights Lab, December 2019, https://pagasa.be/medias/ressourcepublicationitem/31/file/eng/photographing-modern-slavery.pdf.

[6] A White, Media and Trafficking in Human Beings Guidelines, International Centre for Migration Policy Development, Vienna, 2017, https://www.icmpd.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Media_and_THB_Guidelines_EN_WEB.pdf.

[7] W Arthur, Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy, University of Michigan Press, Michigan, 1994.

[8] E Krsmanovic, ‘Captured “Realities” of Human Trafficking: Analysis of photographs illustrating stories on trafficking into the sex industry in Serbian media’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 7, 2016, pp. 139–160 https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121778, R Bleiker and E Hutchison, ‘Fear No More: Emotions and world politics’, Review of International Studies, vol. 34, 2008, pp. 115–135, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210508007821.

[9] S Hepburn and R Simon, Human Trafficking Around the World: Hidden in plain sight, Columbia University Press, New York, 2013; A Lewnes (ed.), Child Trafficking in Europe: A broad vision to put children first, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, 2008, retrieved 17 September 2020, https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/ct_in_europe_full.pdf; A Gearon, ‘How Trafficked Children Are Being Hidden Behind a Focus on Modern Slavery’, The Conversation, 19 January 2018, https://theconversation.com/how-trafficked-children-are-being-hidden-behind-a-focus-on-modern-slavery-87116.

[10] Kennedy.

[11] J Lentfer, ‘Yes, Charities Want To Make An Impact. But poverty porn is not the way to do it’, The Guardian, 12 January 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/voluntary-sector-network/2018/jan/12/charities-stop-poverty-porn-fundraising-ed-sheeran-comic-relief.

[12] E de Bruijn and L T Murphy, ‘Trading in Innocence: Slave-shaming in Ghanaian children’s market fiction’, Journal of African Cultural Studies, vol. 30, issue 3, 2018, pp. 243–262, https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2017.1321982.

[13] M Wilson and E O’Brien, ‘Constructing the Ideal Victim in the United States of America’s Annual Trafficking in Persons Reports’, Crime, Law and Social Change, vol. 65, no. 1, 2016, pp. 29–45, p. 42, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-015-9600-8.

[14] O Soret, ‘Child Trafficking in India: Give voice to the voiceless’, Humanium, 5 April 2018, https://www.humanium.org/en/child-trafficking-in-india.

[15] V B Cvetkovic and D C Olson (eds.), Portrayals of Children in Popular Culture: Fleeting image, Lexington Books, Lanham, 2012.

[16] J Nathanson, ‘The Pornography of Poverty: Reframing the discourse of international aid’s representations of starving children’, Canadian Journal of Communication, vol. 38, no. 1, 2013, pp. 103–120, p. 103, https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2013v38n1a2587.

[17] M Dolinar and P Sitar, ‘The Use of Stereotypical Images of Africa in Fundraising Campaigns’, European Scientific Journal, vol. 9, no. 11, 2013, pp. 20–32, https://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/view/965.

[18] D Zane, ‘Barbie Challenges the “White Saviour Complex”’, BBC, 1 May 2016, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-36132482; J Schaffer, ‘Poverty Porn: Do the means justify the ends?’, Nonprofit Quarterly, 10 June 2016, https://nonprofitquarterly.org/poverty-porn-do-the-means-justify-the-ends; L Murdoch, ‘“Poverty Porn” and “Pity Charity” the Dark Underbelly of a Cambodia Orphanage’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 June 2016, retrieved 23 March 2021, https://www.smh.com.au/world/poverty-porn-and-pity-charity-the-dark-underbelly-of-a-cambodia-orphanage-20160602-gpacf4.html.

[19] M A Holly, Past Looking: Historical imagination and the rhetoric of the image, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1996, p. 11.

[20] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime for the GCC Region, Human Trafficking Toolkit for Journalists, United Nations, 2017, retrieved 16 September 2020, https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/2018/Toolkit_HT_Final_Book_Finish_2017_English_comp.pdf; Taylor and Latonero.

[21] ‘Child Trafficking in Bolivia’, Save the Children, 1 August 2016, retrieved 15 September 2020, https://youtu.be/WhpLYrKWPmo; ‘These Are the Voices of Child Trafficking’, Save the Children, 2 July 2018, https://youtu.be/g0nO6hfkh9Q.

[22] IOM Ghana, Standard Operating Procedures to Combat Human Trafficking in Ghana with an Emphasis on Child Trafficking, IOM Ghana, October 2017, https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/sop_ghana.pdf.

[23] Global Action against Trafficking in Persons and the Smuggling of Migrants, Hear Their Voices. Act to Protect. – Testimonies by victims of human trafficking from around the world, October 2017, https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/GLO-ACT/GLOACT_Victim-Testimonies_October_2017.pdf; H-R Murray, Voices: Ideas for using survivor testimony in antislavery work, University of Nottingham Rights Lab, October 2019, https://www.antislaverycommissioner.co.uk/media/1336/voices-ideas-for-using-survivor-testimony-in-antislavery-work.pdf; A R Sandrolini, ‘The Story of a Survivor of Child Sex Trafficking’, The Exodus Road, 12 April 2019, https://blog.theexodusroad.com/kelly-dore-story-of-survivor-of-child-sex-trafficking.

[24] S Warrington with J Crombie, The People in the Pictures: Vital perspectives on Save the Children’s image making, Save the Children, 2017, p. xi, https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/12425/pdf/the_people_in_the_pictures.pdf.

[25] D Brennan and S Plambech, ‘Editorial: Moving Forward— Life after trafficking’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 10, 2018, pp. 1–12, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201218101; E Shih, ‘Freedom Markets: Consumption and commerce across human-trafficking rescue in Thailand’, Positions, vol. 25, issue 4, 2017, pp. 769–794, https://doi.org/10.1215/10679847-4188410.

[26] H K Golo and I Eshun, ‘“Re-trafficking” in the Coastal Communities and the Volta Lake of Ghana: Children’s rights, agency and intra-household bargaining position’, American Journal of Business and Society, vol. 4, no. 4, 2019, pp. 97-107.

[27] S Okyere, ‘“Shock and Awe”: A critique of the Ghana-centric child trafficking discourse’, Anti-Trafficking Review, issue 9, 2017, pp. 92–105, https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121797.

[28] G Freduah, ‘Poverty Mitigation and Wealth Creation Through Artisanal Fisheries in Dzemeni Area at Volta Lake, Ghana’, Master of Philosophy Degree in Resources and Human Adaptations, Department of Geography, The University of Bergen, Norway, 2008, p. 83, https://bora.uib.no/bora-xmlui/handle/1956/3051; J Fisher, ‘New Research Indicates High Prevalence of Child Trafficking and Slavery-Like Conditions in Ghana Fishing Villages’, Free the Slaves, 28 February 2017, retrieved 23 March 2021, http://www.freetheslaves.net/new-research-indicates-high-prevalence-of-child-trafficking-and-slavery-like-conditions-in-ghana-fishing-villages.

[29] Y Hakim, ‘Ghana’s Child Labourers’, BBC World News, 3 February 2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/n3ct0bxk.

[30] J Snell, ‘Paradise Lost: The dark secrets of Ghana's Lake Volta – in pictures’, The Guardian, 15 December 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2020/dec/15/paradise-lost-dark-secrets-ghana-lake-volta-child-labour-in-pictures.

[31] L Coorlim, ‘Child Slaves Risk Their Lives on Ghana’s Lake Volta’, CNN, February 2019, https://edition.cnn.com/interactive/2019/02/africa/ghana-child-slaves-intl/.

[32] H Siddique, ‘Child Sexual Abuse in Schools Often an Open Secret, Says Inquiry’, The Guardian, 17 December 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/dec/17/child-sexual-abuse-in-schools-often-an-open-secret-says-inquiry.

[33] Y Roberts, ‘“We Were Abused Every Day.” Decades on, children’s homes victims wait for justice’, The Guardian, 18 February 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/feb/08/care-home-victims-wait-for-justice-decades-on-institutional-child-abuse.

[34] O Bowcott and H Sherwood, ‘Child Sexual Abuse in Catholic Church “Swept Under the Carpet”, Inquiry Finds’, The Guardian, 10 November 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/10/child-sexual-abuse-in-catholic-church-swept-under-the-carpet-inquiry-finds.

[35] R Freedman, ‘NGOs Need to Step up and Keep Children Safe – here’s what they can do’, The Conversation, 13 February 2018, https://theconversation.com/ngos-need-to-step-up-and-keep-children-safe-heres-what-they-can-do-91722; A Macleod, ‘When It Comes to Child Sex Abuse in Aid Work, the Oxfam Revelations Are Just the Tip of the Iceberg’, Independent, 10 February 2018, https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/oxfam-aid-work-prostitutes-un-workers-child-sex-abuse-harassment-dfid-a8204526.html.

[36] L Branham, ‘The Deep Place’, International Justice Mission, 16 November 2017, https://vimeo.com/243189898.

[37] J M Morse, ‘Approaches to Qualitative-Quantitative Methodological Triangulation’, Nursing Research, vol. 40, issue 2, 1991, pp. 120–123, p. 122, https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199103000-00014.

[38] V Braun and V Clarke, ‘Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 3, issue 2, 2006, pp. 77–101, https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

[39] C Theron, ‘Can Child Labour Be Justified?’, Ardea International, 2 September 2016, https://www.ardeainternational.com/thinking/can-child-labour-ever-justified-vic-manzano-clt-envirolaw.

[40] C Pollitt and G Bouckaert, Public Management Reform: A comparative analysis – Into the age of austerity, 2nd Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004.

[41] A W Brian, ‘Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events’, The Economic Journal, vol. 99, issue 394, 1989, pp. 116–131, https://doi.org/10.2307/2234208.

[42] I Greener ‘The Potential of Path Dependence in Political Studies’, Politics, vol. 25, issue 1, 2005, pp. 62–72, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2005.00230.x.

[43] S Sontag, On Photography, RosettaBooks, New York, 2005.

[44] G Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign power and bare life, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1998; Kennedy.